John Frazier – Prisoner of War, Hero by John Frazier, Jr.

Personal and societal beliefs and principles certainly change with time. Sometimes people are shocked or amazed to hear stories of people or events from the past, yet these tales may not be so difficult to comprehend if we’re able to empathize, and put ourselves back into that situation and moment in history.

PRE-WAR

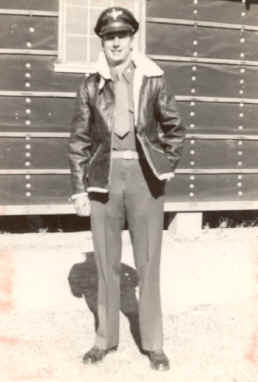

John Frazier Sr, 1944

It takes a special type of person to join the military today to defend our country. One recruiter has stated that only 0.4% of our young Americans enlist. In that context, many of us may find it difficult, or even inconceivable to go back in our minds to 1943, to the middle of World War II, when our very freedom was being seriously threatened on two fronts by the Axis powers, mainly Germany, Japan, and Italy. My father was a student at Plattsburg State Teachers College (as it was known then) and was in the Army reserve program. After completing 3 ½ years at the college, he enlisted in the Army Air Force (the Air Force didn’t become a separate branch until 1947) to become a bombardier on the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, a 4-engine propeller driven bomber using the controversial Norden bombsight. The controversy was that the bombsight was highly technical, yet somewhat inaccurate; while its manufacturer claimed it could drop a bomb into a barrel from 10,000 ft., our bombardiers had many difficulties at times even coming close to their targets. Before the war began, the Germans had access to the Norden’s blueprints, yet rejected it for a simpler, yet more effective bombsight.

After graduation from bombardier school in Nevada, my father was sent to Shipdham, England, where he served in the 44th Bomb Group, 66th Squadron, of the Eighth Air Force. In one more incident that may be foreign to the thinking of so many today, my father’s first (and only) flight on Dec. 4, 1944 did not require a bombardier, so he requested that the pilot bump one of the waist gunners on the plane so that he could take that man’s place instead on that mission. The plane was never able to complete its mission. One engine on the left side was hit by flak, and the other quit after mechanical trouble. The pilot turned around to head back home, and the bombs and most extraneous weight was dropped in farmers’ fields. Altitude dropped from 12,000 to 8,000 ft., and they flew almost 200 miles without problem, but as they got 50 miles from the Rhine River, they started to receive more flak, and the plane was approached by six ME-109 German fighter planes. The pilot gave the “bail out” order. Two crew members perished, six others, including my father, became prisoners of war, and one was listed as missing. Had my father been up in the nose of the plane, where the bombardier is normally located, he also would have been killed that day.

B-24 Liberator

CAPTURE

My father was knocked unconscious for about five minutes when hitting the ground after parachuting from the plane. When he came to, he had already been stripped of his watch, pistol, money, survival kit, and anything else the Nazi soldiers wanted. By the time of his first serious interrogation, he was amazed to discover that the Nazis already knew the number of his plane, the names, ranks, and ID numbers of all of the crew members, as well as all of my father’s personal information. Needless to say, they were extremely efficient, and wanted to make sure that each prisoner knew that.

After a few stays at temporary detention centers with some rather unpleasant living conditions, the crew began their trek by train to permanent internment at Stalag Luft I near Barth, a small town on the Baltic Sea. While traveling to Barth, the POWs discovered that their guards were their life-lines and their friends, because the guards were the only protection they had from angry German civilians. At one point, civilians were throwing rocks at the POWs passing through.

I read the diary of another waist gunner and POW on that flight who was also imprisoned at Stalag Luft I, as well as other material regarding life in that prison camp. I’ve watched my father’s interview with Hector Allen, and read my father’s POW diary, and I can convincingly state that my father, for whatever reason, downplayed life as a prisoner of war as “no big deal” in his interview with Mr. Allen. While conditions cannot be compared to incidents like the Bataan Death March, he certainly never wanted to talk about his POW experience, which only verifies that it was difficult. There was a standing order in camp that if a POW left the barracks during an air raid, he was to be shot on sight by the guards. My father witnessed these shootings. He spent time in solitary. The normal diet was two slices of toast lightly covered with jam with ersatz coffee for breakfast, two slices of toast lightly covered with oleo with ersatz coffee for lunch, and turnip soup for supper. If they were lucky, on good days there was some horse meat in the soup! During the last three months of the war, when the Nazis became desperate, these food rations and medical supplies were cut. Life in Stalag Luft I may not have been as bad as some of the other atrocities that we’re familiar with, but it wasn’t a walk in the park, either. Life as a POW was merciless. “When do I go home?” “Will I ever go home?” “There are rumors that the Nazis will gun us down, just like they have with other POWs. They wouldn’t do that, would they?” “How much more captivity can we take?” “We’re beginning to die of malnutrition and starvation. Who will be next?” “How many more of us?” As an historical footnote, after the camp was liberated by the Russians, a typewritten copy of a death sentence was found for every prisoner in the camp. The Nazis sought retribution, using the logic that the air corps was responsible for the deaths of German civilians. Life in prison camp was like having a spring implanted inside your gut, and that spring tightened just a little more each day. Military discipline was a necessity within the prisoners, because every day was a test of mental strength and endurance. Not every man was able to withstand the pressure.

LIBERATION

History books tell us that the Russian army liberated Stalag Luft I on May 1, 1945, but the prisoners who were there have a different version of the story. Although Russian forces were approaching the camp, the German Commandant had orders to move the camp to prevent it from falling into the hands of the Russians. On April 30th, the Senior American Officer had several conferences with the Commandant, and told him that the prisoners would not move unless force was used. To put this in perspective, this was the day that Hitler committed suicide. It was obvious to all that the war in Europe was over and the Germans had been defeated. The Commandant agreed to avoid bloodshed. At about 10:00 that evening, the guards turned out all of the lights and marched out of the camp, leaving the gate unlocked. Once again, the unarmed prisoners were placed in a position of fear, as they needed protection from any Germans – military and civilian – from entering the premises. Negotiations for food and protection were made with the Russians, and within a week, evacuation had begun.

LIFE AFTER THE WAR

Like so many other members of The Greatest Generation, my father returned home, resumed his education, finishing up his Bachelor’s Degree and continuing to get a Master’s Degree in Educational Administration. He also took courses, but never completed work, on his doctoral degree. He and his wife, who was also in the education field, settled in Little Falls and raised five children. Mr. Frazier enjoyed 34 years as an elementary school principal within the Little Falls Central School district, and was active in various civic organizations.

John Frazier, Jr. is a member of the Little Falls Historical Society.