The Little Falls Lock 17 Dedication Celebration of 1916 by Angela Harris

Will Go Down in History: Historical Pageant and Lift Lock Celebration Greatest Ever Held in Mohawk Valley. July 4, 1916

The Little Falls Journal and Courier may be forgiven for the hyperbole of its banner headline and sub heading on July 4, 1916. The overflowing pride of the language reflects the premise and themes of The Little Falls Historical Pageant and Lift Lock Celebration. The civic pageants of the first twenty years of the 20th century were testaments to civic pride and patriotism, and Little Falls was no slacker.

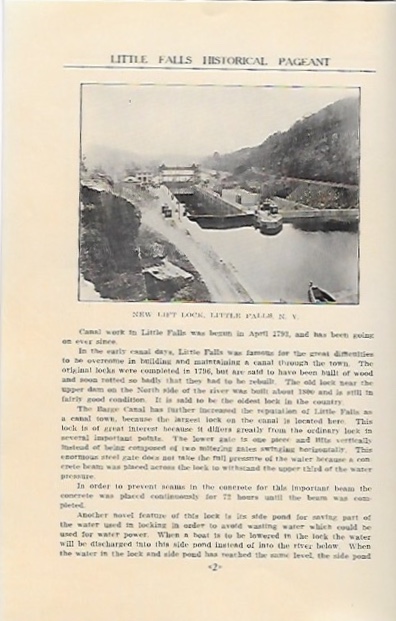

On June 30 and July 1, 1916, The City of Little Falls, New York, was decked out for a major celebration. The opening of the great Lift Lock was a high point in an era of growth and optimism that had included industrial expansion and population growth. Little Falls was a mill city, a center of the circular knitting industry in the country. With mills came workers, and in the twenty years between 1895 and 1915, the City’s population increased from 9,897 to 13,022. Many of these were immigrants or children of immigrants who had come to central New York for work in the factories. The 1910 census listed 7,246 as either foreign-born or children of foreign born. But Little Falls had more than people and factories. The city had churches and schools, an active YMCA, theaters, a hospital and a nursing school, as well as parks and a busy commercial district, stylish homes for the wealthy and rooming houses and tenements for mill workers.

Little Falls had a lot to be proud about in its history as the lift lock (touted as the tallest in the world) launched a new era for the community, and the leaders of the city chose to mount two days of festivities to mark the occasion. The program began on Friday, June 30, with the arrival of Governor Charles Seymour Whitman at 1 P.M. aboard the Empire State Express which stopped at Little Falls for the convenience of the governor. He was accompanied by his military secretary, the State Engineer and Surveyor, the Superintendent of Public Works, The Deputy State Comptroller and Deputy Comptroller, as well as dignitaries from throughout the state and as far away as Chicago.

The party convened with invited guests at the Little Falls Country Club where Congressman H. P. Snyder hosted. About 200 guests enjoyed a “most palatable and appetizing luncheon.”

At 2 P.M. an automobile parade escorted the Governor to the Pageant Grounds located near the current Veterans Field. There Mayor Abram Zoller introduced the governor to launch the public events. “Ladies and Gentlemen: –We have come together to witness a pageant of history.” At 2:30, Whitman spoke. “In keeping with the grandeur of the occasion,” he began, “It is proper and altogether fitting that the Governor of the state should have some part in this celebration that marks the opening of the largest single lift lock in all the world. The Mohawk Valley and the people of the Mohawk Valley have played no unimportant role in the development of New York, and the achievements that you celebrate today are in many respects the very achievements that have earned for us the proud title of the Empire State.” Both men praised the city and the people involved in the planning and execution of the great event. And the pomp and speeches left no doubt about the seriousness and significance of the festivities.

The pageant was presented at 3 on Friday and again at 3 on Saturday after a late morning “Civic and Industrial Parade.”

For all the dignitaries and self-importance of the vision of Little Falls presented that weekend, the Historical Pageant was the jewel in the crown. Historical pageants had been a part of American life from early on. They had evolved through several centuries, but perhaps reached their peak in the first 20 years of the 20th century. Anyone who has seen “The Music Man,” either on stage or film, probably remembers the pseudo-Greek tableau that starred the mayor’s wife and the other society ladies of River City. The Little Falls Lock Pageant was a cousin of that fictional performance, but on a much grander scale. Typically the pageants included large numbers of citizens from the hundreds to the thousands depending on the sponsoring community. Cities such as Philadelphia and St. Louis mounted impressive events usually themed to idealize the origins, history, and accomplishments of the celebrated city. There was even an American Pageant Association that thought to standardize and encourage the pageant movement by holding conferences and publishing a bulletin.

In order to understand the scale of these endeavors, it’s useful to look at the St. Louis pageant of 1914 which is often cited as the epitome of the pageant movement. At the time of this event, St. Louis had a population of just under 700,000. The pageant had a cast of 7,000, and the location was set up for an audience of 70,000 per performance, (Yes, the planners used the population as springboard for their decisions.) In fact, there were 4 performances with attendance at 75,000, 100,000, 90,000, and 90,000. For one rain out, 30,000 were turned away.

With numbers like these, Little Falls’ cast of just under 700 seems paltry. But remember, the population was just over 13,000. That would have translated to a cast of 40,000 in St. Louis—quite impressive.

Little Falls was no slouch in the world of pageants. As part of the original two-day celebration, Little Falls presented an elaborate performance piece written by Josephine Wilhelm Hard of Buffalo. This Historical Pageant of the Mohawk Valley was presented under the auspices of the YWCA and YMCA with help from the Daughters of the Revolution and the Sons of Veterans. And a quick glance at the program reveals names that resonate even now: Feldmeier, Burrell, Dussault, Gilbert, Shall, Gowen, Van Valkenburg, Shephardson, Lansing, Zoller, Snyder, Van Allen,

These pageants glorified the history of the communities that sponsored them by placing current events in the context of the long history and pre-history of the featured cities. They were also interesting in their inclusion of “casts of thousands.” Local people from babes in arms to senior citizens participated in the active tableaux. Scenes from the past were performed with musical accompaniment while poetry provided the settings and explanation for the action.

The Little Falls Pageant was presented in eight “episodes” with a total of 545 individual roles along with 7 committees including 113 members and 12 episode directors, and 15 musicians. With 685 individual jobs in a city with a population of around 12,000 at the time, it was a major involvement. A re-creation of the original event would probably leave the show without enough people for an audience. Little Falls may no longer be able to assemble a cast of hundreds—too many other activities to engage the somewhat less populous community—but there is still no doubt that the canal and the lock have been integral to the life of Little Falls.

Each of the episodes was introduced by the character Father Time. The language is the language of 1916, complete with some word choices and attitudes that are no longer acceptable. And a close examination of the actors shows that there are few of the immigrants who arrived in the Mohawk Valley in the 25 years prior to the Canal dedication, except, or course, for the specifically Polish, Italian, and Slovak people who play themselves in Episode 8.

The eight scenes dramatize the history of Little Falls starting with the pre-history Glacial Period which featured the pot-holes found in the area. The second episode, “The Indian Period,” features Camp Fire Girls as “Indian Maidens,” and introduces the first “white men” to the region in the form of the “Black Coats” or Jesuits from France.

Episode 3, “The Dutch Period” presents cheerful boys and girls dancing as the Dutch people from Schenectady introduces dairy farming and the domestic life of the “White Man” to the native people. Episode 4 is the story of the “English and Palatine Period.” General Schuyler and “his Mohawk Indians” were followed by a delegation from the Palatinate.

Episode 5, “The Colonial Period” highlights William Johnson and his second wife, Molly Brant, a descendant of one of the Mohawks who had visited Queen Anne. This scene is designed to demonstrate the good relations between Johnson and the native people. Episode 6, “The Revolutionary Period,” is the story of the courage of General Herkimer in the Revolutionary War. Episode 7 is the “Period of Peace.” It represents the Mohawk River as the avenue of history in America. And Episode 8, called “The Period of Prosperity” begins with characters representing the thirteen colonies introduced by heralds who are joined by people from foreign lands “as all nationalities combine to make the real American.” As the pageant closes, a personification of Columbia “raises her flag and directs the cast and audience in singing ‘America’.” The Pageant ends with a grand march, Columbia, Uncle Sam and the States leading the way.

It’s unlikely that Little Falls will ever again see anything quite like “The 1916 Dedication Celebration,” but the spirit of community and pride endures in the Little Falls Canal Celebration, a week of fun and reunion for Little Falls in August each year. This year’s 33rd annual event begins on August 9.

Note: Angela Harris is a member of the Little Falls Historical Society.