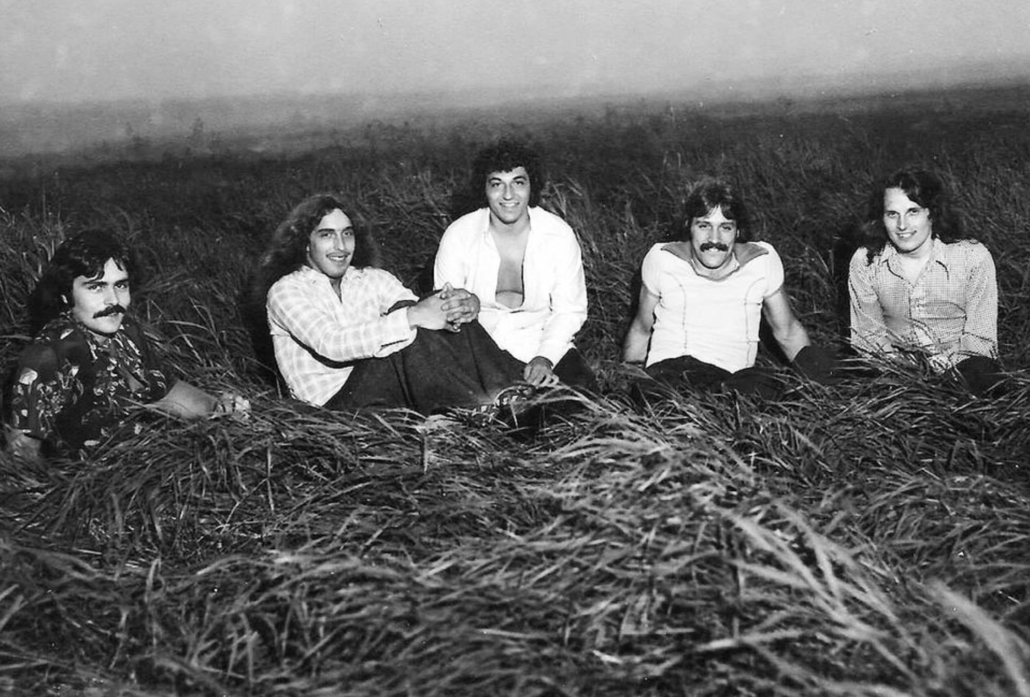

Nearly five decades have passed since I played drums in The Joint Commission and, sadly, many of my memories of that experience have naturally faded away with the passage of time. It’s not that I haven’t tried calling some of them back from obscurity, but there is little to be found in the way of photographs or other documentation of the band’s history. I have however recently had the great pleasure of recounting times in The Joint Commission in telephone conversations with A.J. Campione, our virtuoso lead guitarist, and Fred “Chico” Urich, our capable bassist. I’ve had only a very brief conversation with Mike Walo, our vocalist and sometime rhythm guitarist, and have managed merely to exchange a couple voicemail messages with Bart Carrig, our other rhythm guitarist. It grieves me deeply to add I’ve found no trace of our brilliant keyboardist, Joe “Scoop” Janezic.

All that said, certain images of my association with that band remain immutable among my most treasured recollections, and it is no exaggeration to assert that, though I did not realize it at the time, my lifelong love of blues and jazz found much of its roots in The Joint Commission’s repertoire. Our song list consisted of what then was called “underground rock” because very little if any of it made its way to the Top-40 list or received any commercial radio play, at least not until much later than we first heard and sought to emulate it. Gary and Joe Chapadeau, two of our important musical mentors, introduced much of that music to us. A year or so before our inception, they returned from their pilgrimage to The Summer of Love in San Francisco bearing 33⅓ LP recordings of, among others, such illustrious artists as The Grateful Dead, Big Brother and The Holding Company with Janis Joplin, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Cream and, still among my very favorites, The Electric Flag.

In my view, A.J. and Joe were the heart and soul of The Joint Commission. Without them, the band could not have existed in any form other than perhaps name. Although I don’t recall our employing such terms in those days, they for all practical purposes served jointly as our musical directors and arrangers. Since charts of the songs we played were either unattainable or, more likely, non-existent, Joe, armed with only a legal pad and pencil, ingeniously ferreted out the chord changes and melody lines while listening to the LPs on a portable Victrola. Only occasionally did he check them for accuracy on his keyboard. It wasn’t necessary. The cat had the ears of an elephant.

It can also be said that few if any other guitarists we knew beside A.J. could begin to handle those difficult lead passages laid down by the likes of Hendrix, Clapton, and Garcia. While no one in the band bore the title of leader, it was A.J. and Joe who illuminated our path toward replicating those tunes in acceptable form.

To cite an example of this, I don’t recall our ever daring to perform Manic Depression from the Are You Experienced album in public, but I clearly remember our earnest attempts to learn the tune. Joe and A.J., of course, had their parts down tight as the head on my snare drum, and Chico laid out the baseline in impeccable time. I simply struggled, absent the chops to form the subtly nuanced syncopations and beautifully textured paradiddles underlying Mitch Mitchell’s flawless execution of the song.

“No,” Joe patiently admonished me. “It’s not a four-four, Caesar (that’s what most everybody there called me back then). It’s a waltz. A fast one. Like this: 1-2-3. 1-2-3, 1-2-3,” he said, counting it out while snapping the ones on fingers held high above his ear. A waltz? What self-respecting rock musicians play waltzes? Of course he was exactly correct and, though I was insufficiently experienced to pick up on that obvious fact, I knew I was hearing and trying to play something that resonated within me from my toes to the upper limits of my head, from which I simply could not exorcise the thing. It just kept dancing around in there: 1-2-3. 1-2-3, 1-2-3.

With perfect grace and precision, Redding walked that base line like a razor-thin high-wire. Around his soulful, plaintive phrasings of the lyrics, Jimi sent his lead guitar riffs out in sheet-after-sheet of broad, dense, contra-rhythmic bluesiness, often traversing multiple measures but never failing perfect resolution. They descended upon the underlying pulse of the composition like dark, brooding clouds hovering over a fitfully animated (dare I say manic?) sea, constantly churned by that phenomenal rhythm section comprised of only Redding and Mitchell, and sounding like an ensemble of threefold as many. And Mitchell! My God! His comping of Jimi, though always held sensitively just underneath him, was a seamlessly continuous, brilliantly articulated solo in its own right. Those cats were swinging! And in three-quarter time, no less!

It must have been some years hence, I don’t recall just when, that the epiphany of what I gained from the experience of attempting Manic Depression came to full light in me. True, it was a humbling but healthy revelation of my woefully deficient chops. But it was also the earliest stirrings of my abiding love of jazz. Never do I hear (or am so fortunate to play) those marvelous, up-tempo waltzes in Coltrane’s rendition of My Favorite Things, Wayne Shorter’s Footprints, Chic Corea’s Windows and, of course, Miles’ All Blues, but that I can see Joe flashing that toothy smile from ear-to-ear, and hear him counting out those threes while snapping his fingers squarely on the apex of the ones. And always I hear then, if just for a brief moment, the opening measures of Manic Depression.

Dick “Feldy” Feldmeier, a loyal friend and fan of The Joint Commission, would also have been a wealth of information regarding its history. But we’ve long since lost him to that great concert hall in Rock ‘n Roll heaven exclusively reserved for the genre’s most faithful and devoted disciples. In addition to his generous friendship, Feldy, along with the Chapadeau brothers, also played a profound role in influencing who we listened to and, by extension, what we sought to play. His legendary cellar parties invariably involved introductions to “underground” bands most of the revelers in attendance had never before heard of. All during those momentous events, he served up lush portions of that exquisite ear candy on vinyl LPs (contraband procured in such exotic places as musty, subterranean record shops down in Greenwich Village) spun on his family’s expensive, high-fidelity stereo system.

While having a wonderful time, all the attendees of those occasions were being exposed to the emergence of nothing less than an all-out revolution in popular, as well as not-so-popular “youth music.” But that, as much of the music reflected, was by no means the only revolution under way. The civil rights movement, the women’s movement, the anti- (Viet Nam) war movement, the sexual revolution, the so-called “generation gap,” and the emergence of the “hippie drug culture” were all swelling and converging like some monstrous tsunami. It was a time of confusion, contention, and chaos and, though fallout from nearly every aspect of that crept and sometimes charged into the song lyrics, for me, as I believe it was for the other members of the band, it was always preeminently about the music. The music provided a refuge, a place of beauty and hope amidst fear, ugliness, and despair. And we immersed ourselves in it with full, unwavering devotion.

I can’t say for certain which of us originally spawned the idea for the band, but I believe it was Bart who came up with the cleverly whimsical, double entendre name. It’s spot-on appropriateness left little room for dissent, and there was none. I’d venture, too, that our early organizational meetings occurred somewhere in the vicinity of the lower southeast corner of the no longer present Shopper’s Square, right across from what was then Saint Joseph’s Catholic Church and now is the Community Co-op. I believe this is likely since Adam’s Pool Hall and Dandee Donuts [sic], both located there then, jointly served the better part of Little Falls teens’ social impulses as well as their lust for the vices of billiards and every variety of pimple fertilizing junk food imaginable. Such venues, common in large and small towns everywhere alike back then, I suspect are now all but supplanted by electronic communication devices and the various social media and other applications that run upon them. We, of course, did have telephones at home, but they did not afford the opportunity to don or view the current fashions, their use carried the risk of parental eavesdropping and, while talking on them, you couldn’t very well smoke cigarettes without getting caught.

Due largely to his rigorous practice regimen (with maybe a dash of parental forbiddance thrown in), A.J. did not frequent those venues nearly as much as did the rest of us. But it was probably at one or the other of them that he delivered the much-welcome news that his brother-in-law, Ron DePiazza, as a favor to A.J.’s father, had very generously offered to us as a practice studio the space above Sam’s Super Service, his auto repair establishment. This speaks very loudly of the measure of support A.J., and we as his bandmates, received from his family. We were entitled to use it at no charge until Mr. DePiazza got it leased out to somebody and, fortunately for us if not for him, the market for retail space at that time in Little Falls may as well have descended into the sewers. “The Place,” as we came to call it, now occupied by Yoga and Wellness, was warm and secure, and we could leave all our equipment assembled there, thus avoiding lengthy set-ups and teardowns before and after rehearsals. This afforded precious time for running through another tune or two in the course of a session, precluded our having to impose on our parents to host practice sessions in their homes, and relieved us of the burden of lugging our equipment all over town. It provided much more, however, than all those many practical comforts and conveniences. For me it was a temple, a shrine, wherein the music was the object of our adoration and in which we prepared for our first communion with an audience.

That occurred on a muggy, late-spring Friday evening in the third-floor gymnasium/auditorium at Saint Mary’s Academy. By the time we lugged Joe’s bulky, wood-cased keyboard, the amplifiers, and all the rest of our equipment up those three flights of stairs, we were panting and sweating like we’d just run a marathon. Among the equipment was a makeshift strobe-light Chico and his dad fashioned from a circular piece of corrugated cardboard about five feet in diameter, with a thin slot cut into it, and fixed to an old washing machine motor, behind which was propped a 150-watt floodlight. We set up on the stage and I remember somebody remarking, “Get used to it guys. Next stop is the Ed Sullivan Show,” and somebody else there with us, probably Gordie Ackerman, immediately dropped into his Ed Sullivan imitation, the humor of that providing a much-needed, if insufficient, easing of our nervous tension.

Having set up our equipment and completed our sound check, we watched from one of the third-story windows a promising crowd forming on the sidewalk down in front of the main entrance. Perhaps inspired by the Ed Sullivan imitation, someone suggested we turn the gymnasium lights down as far as possible without arousing the nuns’ suspicions, close the stage curtains, start the strobe-light and, when most of the attendees had filed into the gym, slowly draw the curtains open as we embarked on our first tune of the evening: Purple Haze. Joe led us into the piece and, as the curtains rolled open, the strobe light so blinded me I could only imagine the effect on the audience and the chaperoning nuns.

We were well into the second chorus before my vision adjusted sufficiently to see that nobody danced. It wasn’t their shyness. The audience crowded tightly around the stage, eyes wide and jaws hanging open, having no clear idea what possible role the gyrations of their bodies might play in such an outrageous display of audacity. I didn’t know what to think, but the applause following Purple Haze had not begun to subside before Joe took us right into Fire, followed closely thereafter by Foxy Lady. By then we were breathless and the energy in that gymnasium was more than palpable and, when he called out The Wind Cries Mary, I guessed he thought we needed a “slow one” as much or more than did the audience and the nuns. The whole affair was like an out of body experience, and it was the only gig at Saint Mary’s we were ever again invited to play.

We continued rehearsing and, with much effort, managed to score engagements at the Little Falls High School, the YMCA, and a few other places before landing a gig for a Saint Johnsville High School dance. Our day in the sun had arrived. We were going on the road, albeit for a single performance not ten miles away that paid hardly enough to cover the cost of getting there and back. I had long since forgotten this adventure but, as Chico reminded me in our recent telephone conversation, it did not fare well. For the first and only time we were heckled and booed and, were it not for the merciful intervention of the chaperons, we might well have been tarred, feathered, and run back to Little Falls on one of the rails of the New York Central System.

“What happened? Were we lousy that night?” I asked.

“No, no, no,” Chico replied. “Nothing like that. I thought we played as good or better than ever.”

“Were the acoustics bad?”

“No. Just fine.”

“Well, what happened then?”

“We didn’t perform any Top 10. They were mad because they couldn’t recognize a single song we played.”

So there it was. Avant-garde is never easy. But, selfless and devoted artists that we were, we took it all in philosophical stride, returned to the refuge of The Place, and sought solace in six-packs of Genessee and what we naively (though deliciously) believed was our woefully misunderstood and wrongly persecuted bohemianism.

When I spoke with A.J. a few weeks back, he confessed to forgetting this incident too, then promptly turned to reminiscing about what we agreed was a profound, though subtle sub-textual element at play in our experience in The Joint Commission. Without fully appreciating it at the time, in what we listened to and endeavored to play, we were being introduced to that uniquely American musical art form called The Blues, delivered to us largely by way of England via such luminaries as The Rolling Stones, Cream and, of course, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, to name only a few. Elements of bluegrass came to us by way of Crosby, Stills and Nash, The Grateful Dead, and Moby Grape. And samplers of jazz came via The Electric Flag, Blood, Sweat and Tears and, somewhat later, jazz-rock fusion groups such as Weather Report and The Yellow Jackets. Even country music played a role, as certainly did folk (one had to be living under a rock not to have been blown away by the likes of Bob Dylan and Joan Baez).

What was commonly referred to simply as Rock ‘n Roll back then was in fact a rich smorgasbord of several musical art forms, many having long-established roots in the American Deep South, Appalachia, Memphis, Nashville, Chicago, Detroit, Kansas City, New York City, and so forth. That The Electric Flag subtitled their first album An American Music Band was entirely accurate and appropriate. On their A Long Time Comin’ album, one can hear a perfect example of Chicago-style twelve-bar blues, replete with a full horn section (including bari-sax), in their rendition of Texas and, on the An American Music Band album, a beautifully construed jazz ballad, in which the vocalist is supported by wonderfully delicate and haunting piano comps, in My Woman That Hangs Around the House. The Joint Commission was born and lived its short life in the midst of an incredibly rich and diverse musical milieu, and I am eternally grateful to have been a part of that.

I’ve played in quite a few bands in several places around the country through the years, and still play from time-to-time though, anymore, only in small jazz ensembles or the occasional blues combo. I’m drawn to the fellowship of musicians as much as to the music. Small bands, in my experience, form a sort of perfect, microcosmic democracy. Their participants must master the rules before venturing to break them, and show plausible cause when they do. Players must listen attentively to one another, never speak out of turn and, when speaking, must say something meaningful and useful that genuinely serves the whole endeavor. While one or more of the players may fulfill the role of arranger or musical director, bosses are unnecessary. And unwanted. Everybody knows their part and does their job.

Though we maybe only understood that intuitively, perhaps instinctively, this was no less true in The Joint Commission than any of the finest groups I’ve ever had the honor of playing in. It was a thoroughly wonderful privilege and pleasure. And what a thrill it would be, should we be so lucky to find Joe, to get together once more and undertake a reunion performance. Should such a sacred event ever occur, perhaps I might be extended the chance for absolution by holding up my end of the bargain in Manic Depression.