Over the past two centuries the waterways of Little Falls have undergone major alterations. A Palatine settler or an Iroquois brave from the early days of the village’s existence would find the landscape alien, as conversely would a person from the present day transported back to that time. To realize how drastic those changes have been, one must follow the course of those transformations.

Like most small rivers, the relatively placid Mohawk was complete with small islands, sand bars, deeper holes and jutting points. As it entered the Little Falls stretch, it flowed around a small, barren island which rose just above the waterline. Washed nearly clean of vegetation by frequent rain or snow melt induced flooding, the outcropping would first be named Lock Island and then Hansen Island. From this point the current picked up and surged as the elevation of the river bed dropped 40 feet in less than a mile.

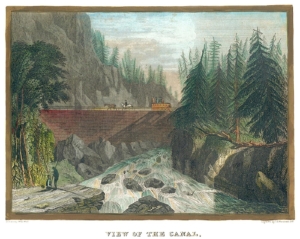

A mid-19th century writer gave a most picturesque description of the rapids, he wrote that the river in Little Falls “goes dashing and bubbling, leaping and tumbling, from rock to rock through the narrow gorge which seems to have been cut expressly for its passage by artificial means.” The rapids smoothed out as the river flowed around a large island, variously known as Rosecrantz Island, Drummond Island and, finally, Seeley Island.

As the river exited the Little Falls section it passed over a very deep hole, of 60 feet or more, and flowed by a large rock outcropping (the northern face of Moss Island) before continuing its eastern journey.

The terrain on the north side of the river was originally must as it is today. From the river’s edge stretched an expanse of flat floodplain. The landscape then abruptly changed to step-like terraces, demarcating past river levels. Beyond rose the northern walls of the Mohawk Valley. From these hillsides a number of small streams (long since routed underground) emptied into the river.

The topography on the southern side of the river was much different than it was on the northern shore. On the upstream (western) end of the rapids, flat “bottom land” mirrored the north side, but as the valley narrowed it gave way to steep rock walls interspersed with massive gneiss outcroppings. At the eastern terminus of the rapids the river was squeezed by a Gibraltar-like mass 40 feet above the water. This feature, complete with circular potholes and the profile of a hatchet-faced man, would become Moss Island. Looming above all of this stone was the precipitous northern face of Fall Hill.

To eliminate the vagaries of the Mohawk River – current, rapids, shallows – the Erie was dug on the south side of the river on a basically parallel route with it. (An earlier canal opened in 1795, the Western Inland Lock, which ran along the north side of the river, was short lived.) Opened in 1825, the Erie was four feet deep and 40 feet wide and was, except for feeder channels, totally divorced from the Mohawk River. The Erie Canal entered Little Falls from the west in what is now the median between Flint Avenue and the highway leading to Route 5S (Route 167). Near the present day guard gates, it jogged slightly to the north then back eastward. At this point it began to descend the 40-foot drop in elevation by means of three locks until it continued on along the course of what is now the road to the Thruway interchange (Route 169). With the Mohawk River on one side and the Erie Canal on the other, Moss Island was born.

In 1841 the Erie Canal was widened and deepened to accommodate increased traffic. The southern channel of the river that swept by Seeley Island was filled in at both ends and incorporated into the “enlarged” Erie. Seeley Island, now existing as an island in name only, was physically joined with the newly formed Moss Island. Feeder channels, which ran from the river to the canal, sliced off another piece of land, which was dubbed Loomis Island. Later, when these feeder channels were filled in, Loomis, Seeley and Moss Islands were combined to form a “super island.” By the mid-1800s there were over 50 buildings located there. Mills, grocery stores, boarding houses, hotels, liveries, slaughterhouses and private residences either catered to canal traffic or made use of the abundant waterpower available.

Further improvements in the following years – an aqueduct that brought canal traffic and better accessibility to more village businesses to a boat basin on the north side of the river, bridges over the canal at Bellinger Street and opposite Lock Island, and wing dams in the river to provide waterpower – also contributed to the changing landscape of the south side of Little Falls.

At the beginning of the 20th century, as the size of freight boats increased and technology replaced the horse and mule as means of locomotion, the need for a much larger canal was again evident. In many locations the footprint of the Erie Canal was enlarged and brought into existence as the new Barge Canal, but in the Little Falls area the Mohawk River served the purpose. The Mohawk River east and west of Little Falls was deepened to at least 14 feet and straightened (islands were dredged out and points of land jutting out into the river were sliced off.) In Little Falls a whole new river/canal channel was dug south of Lock Island, concrete walls were poured, a massive double door guard gate was erected and Lock 17 was built replacing the four Erie Canal locks. Completed in 1918, the Barge Canal lopped off much of Loomis/Seeley/Moss Island displacing many of the buildings on the island. Also, Goat Island was created by the heightened water level. The final product looked much as it does today.

Remnants of the waterways and geography of southern Little Falls remain. The rapids of the Mohawk River, along with ruins of wing dams and waterpower flumes, can be viewed from the Ann Street Bridge. The Western Island guard lock adjacent to Hansen’s Island and Lock 36 of the Erie Canal (just below Lock 17) and a portion of the Erie’s Lock 38 (encased in a wall below Burke Bridge) are well known. And the bed of the Erie Canal can be seen just off Route 167 southwest of the city. But most evident are the ancient rock outcroppings that once stretched from Moss Island across the span of what is now the Barge Canal (once again renamed the Erie Canal in 1992) to the foot of Fall Hill’s cliffs.

The Little Falls Historical Society 2017 exhibits will focus on the bicentennial of the groundbreaking of the Erie Canal and the evolution of our waterways and on the history of music in Little Falls. The museum opens for the season with a reception on May 23.

Editor’s note: David Krutz’s article, “Evolution of the Little Falls,” is the first part of the Little Falls Historical Society’s 2017 writing series. Other articles will follow up until and following the opening of the historical society museum on May 23. Article topics will vary, but each will relate either to the bicentennial of the 1817 groundbreaking for the Erie Canal or to the history of music in Little Falls.