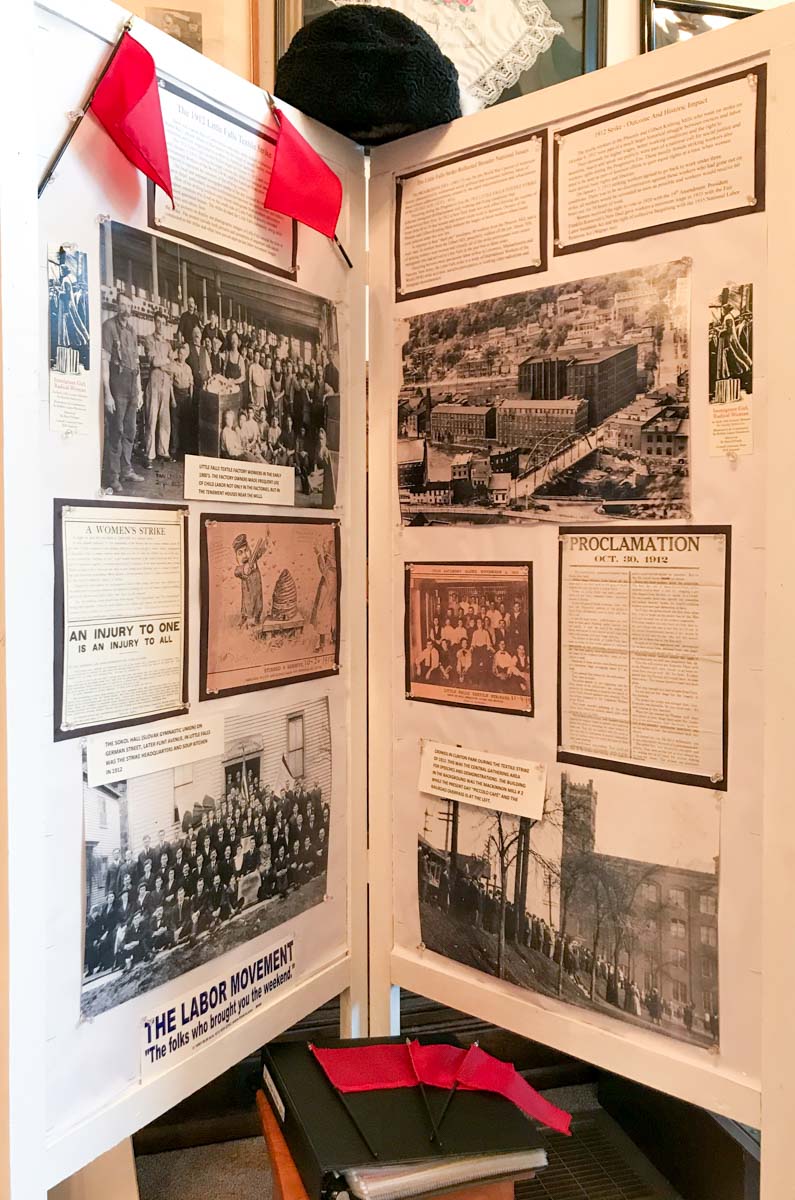

The owners of the Phoenix and Gilbert knitting mills cut the pay of their workers in response to the reduced workweek and the response of their employees was immediate: Short pay envelopes were the impetus on October 9, 1912 for 80 mostly female employees of the Phoenix Knitting Mill and, a week later, 76 workers at the Gilbert Knitting Mill to walk off the job and into history. Desperate people had been driven to desperate action.

Key figures in the Textile Strike included public health nurse turned labor sympathizer Helen Schloss, labor organizer Matilda Rabinowitz, Little Falls Police Chief James “Dusty” Long, Schenectady socialist Mayor George Lunn, and IWW co-founder William “Big Bill” Haywood, but the real heroes were the strikers themselves.

What followed was a bitter and at times violent labor strike against both the Phoenix and Gilbert knitting mills involving over 600 workers and putting Little Falls in the middle of national labor movement events.

The initial response by Little Falls city officials and law enforcement was to side with the mill owners. Chief Long said: “We have a strike on our hands and a foreign element to deal with. We have in the past kept them in subjugation and we mean to keep them where they belong.”

This type of response by city officials drew ever-widening attention and publicity, even from the national media. The refusal of public speaking permits and the breaking up of peaceful labor gatherings in Clinton Park in the early days of the strike inadvertently put out the welcome mat to political activists far and wide. The strikers and their sympathizers had been turned into media martyrs. The IWW and socialists of all stripes came to Little Falls to side with the strikers. Among them were Mayor Lunn and IWW heavyweights Rabinowitz and Haywood. These individuals saw Little Falls as an opportunity to advance national organized labor causes.

The Journal and Courier October 18 headline read: “Arrest Mayor Lunn – Schenectady Socialist in Little Falls Lock-up.” Arrested in Clinton Park for inciting to riot, Lunn had been doing little more than trying to address an assembly of striking workers. The right of assembly and free speech had seemingly been revoked on the streets of Little Falls.

On October 24, 1912 striking workers held a mass meeting and voted to join the IWW; the radical union had become the organizing force behind the Little Falls strike. A strike committee was formed and Little Falls authorities were accused of deliberately inciting riots and then making arrests. One strike committee strategy was to goad police into making mass arrests so that city jails would be swelled to beyond capacity.

Helen Schloss had been brought to Little Falls in May 1912 by the Fortnightly Club to study and help treat tuberculosis outbreaks in the city. By the time of the strike, Schloss had been so taken with the struggles of the working poor that she resigned her post, threw herself into strike activities and became a central figure.

October 30, 1912 was a day of confrontation. The violence ensued when a combination of Little Falls police and special policemen, hired through the Humphrey Detective Agency in Albany, clashed with strikers near the entrance of the Gilbert Knitting Mill. A number of strikers were savagely beaten, one policeman was shot in the leg and another was stabbed.

The strikers then withdrew across the Mohawk River, with many heading to their strike headquarters at Slovak Hall on today‘s Flint Ave. The police followed, destroying some of the building’s contents, roughing up more people and perhaps firing shots into the basement before fanning out across the city to arrest individuals connected with the strike. By day’s end, the entire strike committee, including Schloss and Ben Legere, were in custody. The stakes had been raised and what followed was a two-sided media blitz and more confrontation.