WRITING SERIES: Camp Jolly was the summer place to be

by David Krutz

Most people have never heard of Camp Jolly and those few that have aren’t sure what it was, where it was located or even if it truly existed.

Yet, to the folks living in this area in the mid-1890s, Camp Jolly was widely known and thousands flocked to it as the summer place to be.

However, despite its name, the short-lived life of Camp Jolly ended sadly and led to the undeserved ruination of one man’s aspirations.

Camp Jolly was the dream of Daniel J. Tittle, Jr. In 1893, he moved from Rensselaer to Little Falls to take the position of master mechanic — chief engineer in today’s parlance — at Eagle Mills. Little is known of Tittle’s earlier life other than he was a certified engineer and a licensed riverboat captain on the Hudson River.

Not long after settling in his Church Street home, Tittle began to envision a picnic area and recreation ground somewhere on the Mohawk River in the vicinity of Little Falls. Why Tittle chose such a project is unknown, perhaps he hoped to profit from the energy of the 1890s era, the “Gay Nineties.”

Tittle attacked his vision for Camp Jolly with passion. He leased the grove of C.A. Van Valkenburg, about four miles east of Little Falls. The grounds, which had nearly 10 acres along the waterfront, were bounded by the Mohawk River on the south and the New York Central track line on the north. With the river on one side and the trail lines on the other, the site was easily accessible.

Tittle constructed a landing in Little Falls on the Mohawk River’s north shore near the eastern edge of Moss Island. Here he began building a 48-foot long river steamer, dubbed the Victor Adams, capable of carrying more than 100 passengers. A steam launch, with seating for about 15 people, was also purchased. Conveyance to the park was to be primarily by water.

When spring arrived and the snow melted in early 1894, work on the Camp Jolly grounds themselves began. Bushes and shrubs were removed, downed trees were carted off, the picnic area was mown and walking tails were cut. Docks that stretched 30 to 40 feet into the river were built on the park’s shoreline. A raised and covered dancing platform was erected soon after and a baseball diamond was laid out. To complete the preparations for the season, playground equipment was installed, an archery range was set up and tennis and croquet courts were added.

Camp Jolly officially opened on Aug. 14, 1894.

The Rockton Council of Little Falls hosted a grand opening on that date, which was open to all. “Beefsteak,” clam chowder, steamed clams and green corn headed the menu, while Fallis’ orchestra provided music for dancing.

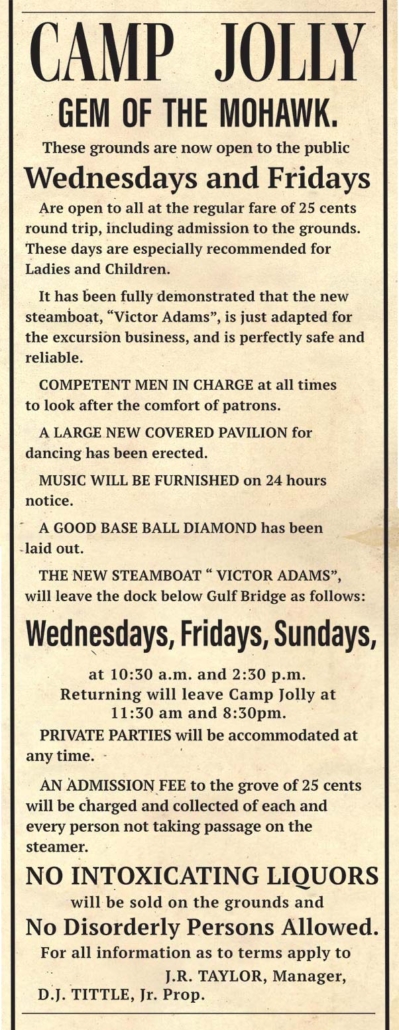

Although the summer season was fast ending, Daniel Tittle flooded the area newspapers with advertisements and puff pieces (the 19th century’s version of infomercials) on Camp Jolly, the “Gem of the Mohawk.” In his ads Tittle made it clear that “no intoxicating liquors would be sold on the grounds and no disorderly persons allowed.”

Open on Wednesdays, Fridays and Sundays, roundtrip on the steamer from Little Falls, which included admission to the park, could be had for 25 cents. In perspective, a common laborer in 1894 earned about 10 cents an hour.

Attendance in the abbreviated 1894 season had been very good so an optimistic Daniel Tittle resigned his position at Eagle Mills and devoted all of his attention to Camp Jolly. In 1895 and 1896, major improvements were made to his venture. A covered dining pavilion with a capacity for 700 diners was erected. A large kitchen, with two brick ovens and an “auxiliary range” were built, as was a “Mother’s Cottage,” complete with cribs and armchairs. Here a weary mom could take her little one for a nap, feeding or just to get away from the hub-bub. A matron was on duty at the cottage at all times. An ice house, with a walk-in food cooler, was added and stocked with 400 tons of ice. Lunches and dinners were served on demand and light refreshments and cigars were always available.

The springs that existed on the grounds were piped so running water was available in the kitchen and to drinking fountains throughout the park. One of the springs provided healthful mineral water that was high in iron. The dancing pavilion was enlarged so 40 “sets could be comfortably sashaying on the dance floor at one time. It was boasted that in case of inclement weather 5,000 people could get out of the rain.

In the recreation area, the baseball diamond was rebuilt making it one of the finest in Central New York. A cinder covered quarter-mile track for bicycle or foot racing was constructed with banked curves for added speed. A steam-powered merry-go-round and “teeter-boards,” which would move in a “whirligig fashion,” were installed. Swing sets were added at convenient places so “girls can take angelic flight under the influence of male propulsion.” At the waterfront, new rowboats were available as were fishing tackle and bait. The steam launch could also be rented for scenic cruises. At its peak. Camp Jolly was employing nearly 100 people.

With such and influx of customers — attendance at the park was approaching 15,000 per season, with the majority sailing on the Victor Adams — Tittle realized he needed more carrying capacity. In the late summer of 1895, he launched his new, double-decked barge the City of Little Falls. The “scow,” which could transport nearly 500 patrons, was properly christened with a bottle of wine broken across its bow. The barge was to be used when unusually large picnic parties were scheduled. The paddle wheel on the Victor Adams was replaced by a propeller to increase its speed and plans were under way to build a new, larger steamer that could carry 700 customers.

Throughout 1895 and 1896, large groups were holding their summer picnics at Camp Jolly. The Ancient Order of United Workmen, the Central New York Liquor Dealers and most granges and church Sunday school groups were using the park. Along with private parties and individual picnic-goers, Camp Jolly was the place to go. Kelly’s and Fallis’ orchestras were regulars, a balloon ascension with trapeze aeronauts was featured and bicycle, running and swimming races with valuable prizes were held.

Baseball games were standard, with a memorable match between the Bailey’s of Little Falls versus the mighty Gilliam’s of Canajoharie. In the hope of winning the tilt, the Bailey’s imported four ringer ball hawks from Syracuse. On another occasion, professional boxers from Syracuse exhibited their skills in four-round bouts. In one bout, Gene Riordan of Little Falls fought a “rattling” scrap with “Chick” Hammond of Syracuse. And, of course, July 4 celebrations were widely attended.

Central New York trains were no making eight scheduled stops at the grove daily. Camp Jolly had become a very large enterprise.

Then, in June 1896, a seemingly unrelated event began the downfall of Camp Jolly.

On June 18, 1896, the boiler on the steam launch Titus Sheard exploded on the Erie Canal near Traylor Diving Park, a few miles west of Little Falls. Twelve people were killed. Horrified spectators at the park watched as horribly mangled bodies were thrown on to the towpath. These eyewitnesses related their stories to anyone that would listen, and area newspapers carried vivid accounts of the tragedy. The fear of riverboat steam travel multiplied, spilling over into the Camp Jolly excursions.

Daniel Tittle stopped all use of his steamers and switched all scheduled parties to travel by rail. He brought in a federal inspector and a steam boiler expert to inspect his craft, which were found to be in top notch conditions, but customers were still loathe to use his steamers. Tittle even offered to transport all of his patrons on his barge, towed by the Victor Adams and thus a distance from the steam boiler, but it all was to no avail and business dried up.

Camp Jolly remained open throughout the rest of 1896 and into the 1897 season, with limited success, but its days were numbered. Its major source of interest and income had been the river excursions and area people were afraid to use steamboats. As a side note, Taylor Driving Park soon closed for similar reasons.

It appears Daniel Tittle abandoned Camp Jolly soon after the 1897 season. He had expended a great deal of money, time and effort in developing his dream and, through no fault of his own, it had all come to naught. Tittle sold his boats, closed the park and moved back to Rensselaer where he once again became a steamer captain on the Hudson River.

Daniel J. Tittle, Jr. died in 1908 at the age of 51. Members of the Rockton Council of Little Falls attended the funeral of a “kindly, big-hearted man who made friends of all who came to know the inner qualities of his nature.”

No material remnants of Camp Jolly exist today — the grounds have been farmed and logged — however, its bright, but brief memory remains, not as a myth but as a very real place in Little Falls history.

David Krutz is a member of the Little Falls Historical Society.

This article can be viewed on the Times Telegram.