A SAILOR AT HEART | THE LIFE STORY OF CHARLES P. BYRON

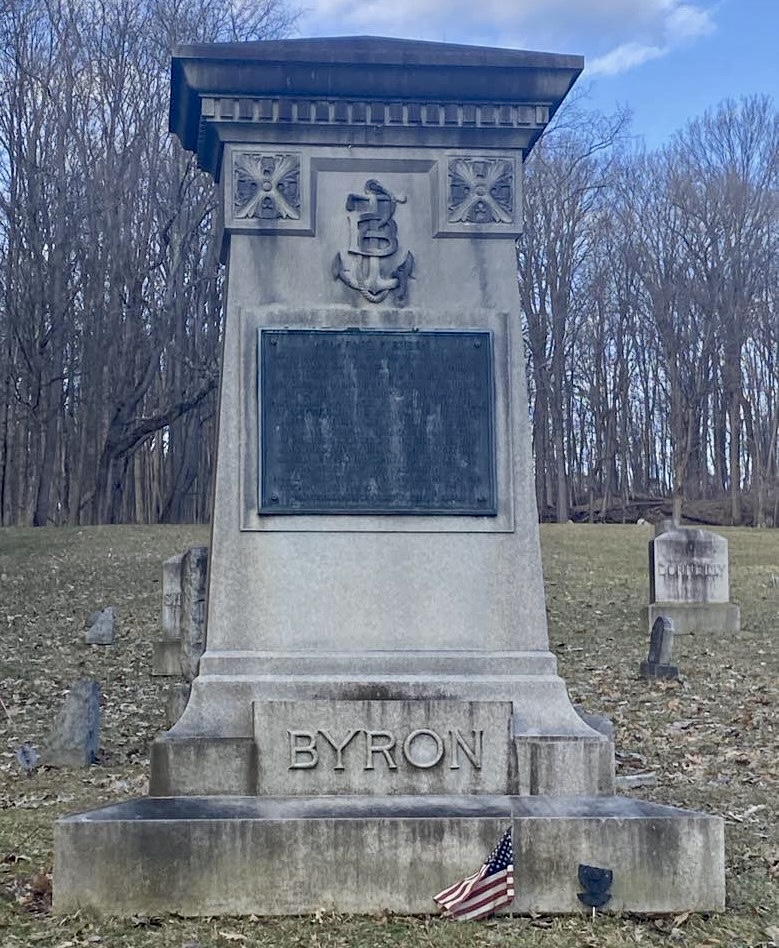

OLD ST. MARY’S CEMETERY

The prelude to the life story of Charles P. Byron begins as one walks through the entrance of the Old St. Mary’s Cemetery. The entrance to this historic cemetery is marked by columns and a mausoleum of moss-covered, locally quarried limestone at the end of Sherman Street, in Little Falls, New York.

Old St. Mary’s Cemetery was created by St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in 1864 and was enlarged with land purchased for the sum of $500 on the 21st of November in 1870 from Corporal James Kenna. The cemetery was enlarged for a second time with an additional ten acres purchased for the sum of $1,200. on the 16th of May in 1905 from Charles T. Wilcox.

The remembrance stones in Old St. Mary’s enchanting graveyard are marked with age and were carefully put into place many years ago. These stones, engraved with a loved one’s name, grace a well-worn roadway that meanders over the steep, terraced hillside.

Old St. Mary’s Cemetery is an alluring place to explore, as it feels like it should be tucked in amongst the hills of the “old country” of those who lie buried here.

As one follows the roadway uphill with due respect, one will be led to the back of the cemetery to a grand monument proudly positioned on a terrace near the summit. Being of considerable size, the pillar-like structure was erected for an Irish immigrant, Charles P. Byron.

The Byron Monument

The stately Byron monument stands vigilantly at the foot of the Byron family plot, where Charles P. Byron and the family he cherished lay slumbering in their last sleep. For one to enjoy the hilltop view that Old St Mary’s Cemetery holds, one must follow a grass path another hundred yards or so beyond the Bryon monument to the summit. Charles P. Byron did well in choosing this resting place for himself and his family, as the breathtaking view from the summit overlooks the city below that he called home.

Summit View

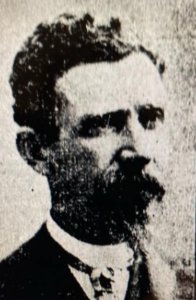

CHARLES PATRICK O’BYRON

Charles Patrick Byron 1844-1912

The life story of Charles P. Byron begins with Charles’ birth taking place on St. Patrick’s Day, a saint’s day, from which he must have been gifted the luck of the Irish. Charles was born in Ennis, County Clare, Ireland, on the seventeenth of March in 1844, as Charles Patrick O’Byron. His beloved mother, Ellen McGarth O’Byron, was buried in the local cemetery in Ennis in 1849, during the Great Potato Famine of Ireland. As a mere lad of the age of five, Charles set out on his first adventure by sailing across the Atlantic Ocean. On this maiden voyage, the sea cast a spell over Charles that embraced his heart and would stay with him for many years to come.

FINDING HOME

Charles left behind the village of his birth with excited anticipation of the adventure that lay before him. He, along with his father and six siblings sailed for America, searching for a new place to call home. The O’Byron family entered Ellis Island, Port of New York, on the 18th of September in 1849.

The O’Byron family found their way to the Mohawk Valley and set about transplanting their family roots within the village of Little Falls. At some point, after the family arrived in America, Charles’s father Thos O’Byron, employed as a day laborer in the village mills, changed his name to that of Thomas O’Byron.

Thomas found a place for the family to call home, a house on the south side of German Street in the South Side section of Little Falls. Thomas, then employed as a stone mason, purchased the land lot of 79 German Street from Arphaxed Loomis for $160. on the 7th of October of 1856. German Street is known today as Flint Avenue in honor of Corporal Albert Nemyre Flint, the first Little Falls serviceman to lose his life during World War I.

After mourning the loss of his wife for many years, Thomas married for the second time, taking Mary Ann O’Hara as his wife in 1864. Through this marriage, Thomas gained two stepchildren, Thomas and Catherine O’Hara.

Charles spent half of the day of his adolescent years at school, most likely at the neighborhood school on Jefferson Street, while working the other half of his day in the local paper mills. Charles was an intelligent lad and an avid reader, gaining much knowledge on many subjects.

A SAILOR AT HEART

At the age of fourteen, Charles, being an adventurous lad by nature, decided to leave home. He joined on board a whaling ship where he acquired knowledge through first-hand experiences of the laborious duties that it took to become a sailor. Charles became drawn into the life of a mariner and after spending close to three years at sea, he returned to Little Falls.

During Charles’ time at sea in the mid-1850s, the United States whaling industry used gun-loaded harpoons and steamships as they fished the Atlantic Ocean, along the East Coast for right and humpback whales. The main product sought from whales was oil, which was processed and bottled on board the whaling ship. Whale oil, called lumera, was in high demand for lighting. Another use for whale oil was for lubricating the machinery of the emerging Industrial Revolution. The textile industry used whalebone in the manufacturing of corsets for women. The whalebone, known as baleen plates, is a food filtration system in the upper jaw of a toothless right whale.

Charles was soon to embark on yet another adventure back at sea, this time in the Indian Ocean as a sailor aboard a merchant ship, the Cavaller. The Cavaller was stricken by a typhoon after a short time at sea and shipwrecked on the shore of Mauritius Island. Mauritius Island is a tiny British colony about 1,100 miles off the shore of the southeastern coast of East Africa, just east of Madagascar. After remaining on the Island for several weeks, the maritime crew was discovered. They were rescued by a passing British ship that delivered them safely to Liverpool, England.

Merchant ships, like the Cavallar, were the backbone of the 1800s with their use for commerce and communications as they sailed from one port to another. These vessels also played a major part in immigration, with the O’Byron family sailing from Liverpool, England, to the Port of New York on board the merchant ship, the Kingston. Nearly two million Irish immigrants sailed on merchant ships during the two-month-long journey to America from 1846 through 1852, fleeing from the Great Potato Famine of Ireland. Over five thousand merchant ships made this voyage carrying immigrants across the Atlantic Ocean during this period. Many of these vessels only had crude accommodations for the immigrants amongst the cargo that was carried on board.

In the early 1800s, Little Falls received an influx of Irish immigrants, with many hand-digging the trench for the Erie Canal. Many Irish families stayed within the village, with the Irish community being the major financial benefactors of the construction of Old St Mary’s Cemetery in 1864 and St. Mary’s Church from 1873 to 1879.

A SAILOR AT WAR

Soon after Charles arrived back at Little Falls, a war arose between the states of the North and the South. Charles chose to fight in the American Civil War to defend the state that he embraced as his own. He enlisted at the age of seventeen, in the United States Navy on the 4th of May in 1861, along with many of his Cavallar crewmates, as the U.S. Navy was racially integrated. Charles was sworn in as United States Navy Seaman Charles Patrick Byron, eliminating the “O” from his last name.

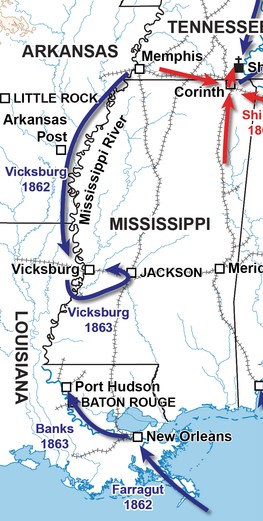

THE ANACONDA PLAN

Map of the Mississippi River Battles | The Vicksburg Campaign.

Two of the main tasks of the United States Navy during the Civil War were to take control of the Mississippi River in order to divide the Confederacy east and west and to blockade southern ports to prevent exporting cotton to European markets to gain much-needed revenue. These strategies were referred to by Lincoln as the Anaconda Plan to both divide and strangle the Confederacy. Byron played a part in this plan.

U.S.S. PENGUIN

THE BATTLE OF PORT ROYAL

In 1861, Byron received an assignment to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron on board the warship, the U.S.S. Penguin, with the task of blockading the Atlantic coast from the Confederacy. The U.S.S. Penguin participated in the capture of Fort Walker, at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, and Fort Beauregard, at Harrisonburg, Louisiana. The U.S.S. Penguin was one of the first vessels to do duty in the war at Port Royal, South Carolina, with the Union securing the Port Royal Sound. The Union used this port to refuel and resupply the fleet of the United States Navy.

A NAVAL HOSPITAL SHIP

THE NEW WORLD

On the 24th of December in 1861, Byron was admitted as a patient by Sgt. Joseph Hugg, as hospital ticket no.9335 on board the Navy hospital ship, the New World. Byron had contracted a contagious illness known then as Rubeola, a near-death case of measles. During his hospital stay, he was medicated for his symptoms with port wine, whiskey, and other expectorants, tongue cleansing salts, and poultice body washes. The personal items that he had with him when he was admitted to the hospital were; one hammock, 2 blankets, 1 mattress, 1 bag, 1 coat,1 jacket, 4 trousers, 2 frocks, 2 flannel shirts,1 pair of stockings, 1 pair of boots, 1 handkerchief, and 1 cap.

During Byron’s illness, the New World was anchored in the Chesapeake Bay at Fortress Munroe, Virginia. During the war, this fort was used by the Union to house refugee slaves, who were classified as “contraband of war,” being the captured property of the Confederacy. The Federal Army used the slaves as paid laborers to support their war efforts.

On the 12th of February of 1862, after fifty days in medical confinement, Byron was discharged from the hospital and ready for duty.

U.S.S. ONEIDA

ADMIRAL DAVID GLASGOW FARRAGUT

Upon leaving the hospital ship in mid-February of 1862, Byron was assigned to the West Gulf Blockading Squadron on the gunship, the U.S.S. Oneida, under the command of Admiral David Glasgow Farragut. The U.S.S. Oneida weighed 1,032 tons, was armed with nine war guns, and was amongst a fleet of seventeen three-masted, screw-sloop-of-war steamers. The flotilla was split into three columns and was led by the U.S.S. Hartford, the twenty-five-gun flagship of Admiral Farragut. Farragut was under secret instructions to command the blockade squadron along the Mississippi River, under orders from his foster brother Admiral David Dixon Porter. Farragut’s orders were to help the Federal Army take control of the Mississippi River as part of the Vicksburg Campaign, as it was the primary shipping route for commerce and communications for the South and a supply line for the North.

THE BATTLE OF HAMPTON ROADS

In 1861, the Confederates salvaged the sunken U.S.S. Merrimac and reconstructed the ship with two layers of two-inch thick iron armor plating, creating the South’s first ironclad warship, which they rechristened as the C.S.S. Virginia.

The Battle of Hampton Roads began on the 8th of March in 1862, with the ironclad C.S.S. Virginia pursuing Farragut’s blockading vessels. The ironclad warship destroyed two wooden warships of the Union’s fleet. The following day, on the 9th, the C.S.S. Virginia battled against the Union’s U.S.S. Monitor, being the first battle in history between two steam-powered ironclad warships. The warships battled for hours, before reaching a stalemate, with neither side claiming victory.

After the Battle of Hampton Roads, the fleet of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron sailed to the Mississippi River through the Gulf of Mexico. Hampton Roads is a roadstead formed from the intersection of three rivers, the Elizabeth River, the Nansemond River, and the James River. A roadstead is a naval term for a body of water that has no rip tide currents or ocean swells, where a ship can safely anchor without worry of drifting or damage. Hampton Roads forms into a channel that flows into the Chesapeake Bay, and then its waters empty into the Atlantic Ocean.

THE BATTLES OF FORT JACKSON AND FORT ST. PHILLIPS

Farragut arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi River, just south of New Orleans, with an armament of one hundred heavy guns, seven hundred U.S. Navy sailors, and eighteen warships. On the 18th of April in 1862, Farragut’s fleet fired upon Fort Jackson, at Jackson, Tennessee, and Fort St. Phillps, at Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. After two days of heavy gunfire at the forts, a surrender from the Confederates was still not forthcoming. After inflicting serious damage to the forts, Farragut chose to direct his fleet to move up the Mississippi River towards New Orleans.

FLAMES OF C.S.S. GOVERNOR MOORE

As Farragut’s fleet passed by the forts near dawn on the morning of the 24th of April in 1862, they came upon the C.S.S. Governor Moore, a schooner-rigged gunboat of the Confederate Army, and a flotilla of Confederate warships. A gun battle ensued, with Farragut’s fleet causing serious damage to the C.S.S. Governor Moore. The Confederate captain of the C.S.S. Governor Moore set the boat afire as it was drifting along the shoreline of the Mississippi, with the intention of it to blow so that it couldn’t be captured by the North. Most Confederate ships that participated in this battle were sunk, with the two Confederate forts surrendering on the 28th of April in 1862. Farragut lost four Union warships during this battle.

THE BATTLE OF NEW ORLEANS

The U.S.S. Oneida held the position of fourth ship in the first division led by Farragut up the Mississippi River to the city of New Orleans, the home of Farragut’s childhood. Even though Farragut grew up in the South, he regarded secession as treason. During the war, New Orleans was declared a neutral area and was ordered to surrender on the 25th of April in 1862. On the 27th and 28th of April in 1862, the U.S.S. Oneida destroyed Confederate obstructions on the Mississippi River, helping the Union set a path for a victory at Vicksburg. The Union captured New Orleans, one of the most important cities of the South due to its large naval base, on the 1st of May in 1862.

THE BATTLE OF BATON ROUGE

Also, on the 25th of April in 1862 the Confederate government of Louisiana abandoned the city of Baton Rouge, hoping to make a temporary capital in Opelousas, Louisianna. The Confederates didn’t want the North to capture the cotton and liquor that would be left behind, so they doused all the cotton bales in the area with liquor and set them afire. On the 9th of May, Baton Rouge fell to Farragut’s Navy fleet, without any resistance from the Confederates. The Confederates tried to take back the city on the 5th of August in 1862, which began the Battle of Baton Rouge. The Confederates had hoped to move the Union Army out of Louisiana but failed. Mary Todd Lincoln lost her Confederate half-brother, Lieutenant A. H. Todd during this battle.

Byron received “congratulations of the Navy Department, the Government, and the Country for Courage and Daring in letters from Washington dated May 10th, 1862” as stated in his epitaph, for the bravery demonstrated during the attacks on Fort Jackson, Tennessee, and Fort St. Phillips, Louisiana, and the destruction of the Confederate warship, the C.S.S. Governor Moore.

THE BATTLE OF VICKSBURG

During the siege of Vicksburg, the battle in which the North secured the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River, Byron held the honorable position of an oarsman, relaying messages from ashore to Farragut’s fleet during the forty-seven-day siege. The U.S.S. Oneida was anchored one and a half miles below the city of Vicksburg during the siege. Confederate Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton surrendered the city of Vicksburg on the 4th of July in 1863 to U.S. General Major Ulysses S. Grant. This Union victory split the South into two, east and west, with the Federal Army taking control of the Mississippi River, a triumph for the U.S. Navy. For this accomplishment, Congress honored Farragut with a promotion to rear admiral. Farragut was the first Navy officer to serve as rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral throughout his military career in the United States Navy.

Battle of Vicksburg

A TURNING POINT FOR THE UNION

Admiral David D. Porter states that he was present when then-President Abraham Lincoln stated “… Vicksburg is the Key…Let us get Vicksburg and all that country will be ours. The war can never be brought to a close until the key is in our pocket… “while viewing maps and planning the Vicksburg Campaign, in November of 1861.

The Union claimed victory at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania the day before on the 3rd of July in 1863. The combination of the Union victories, at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, was considered a turning point for the Union during the Civil War.

Byron was honorably discharged from the U.S. Navy on the 18th of July in 1863, returning to Little Falls once again.

LITTLE FALLS IN THE CIVIL WAR

A total of five hundred and eighty-three men served under the Union flag from Little Falls throughout the four years of the Civil War. Little Falls lost seventy of those brave men to battle wounds and disease, or in Confederate POW camps. Many of the Civil War Veterans of Little Falls are buried in the Fair View Cemetery, along with the grave of the “Unknown Soldier” who fell from a passing train in 1862.

A WAGON TRAIN WEST

It wasn’t long before Byron was off on yet another adventure, this time to the plains of the West on a wagon train. After many hardships, Byron’s wagon train reached Kansas, with him only staying for a short time before heading back East.

Most likely, Byron had taken the Oregon Trail to Kansas, with the trailhead beginning at Independence, Missouri. There’s a possibility that Byron was hired to drive a team of oxen by a family heading west, with the average miles covered by a wagon traveling along this route in the 1860s, under good conditions, was fifteen miles per day. Many settlers took this trail west to claim land through the Homestead Act of 1862, signed into place by then-President Abraham Lincoln, which was intended to develop the American West. Any United States citizen above the age of twenty-one, excluding Confederate soldiers since they had taken up arms against the government, could lay claim to a six-square-mile plot of one hundred and sixty acres, called a township. Claimants would have to apply for ownership of the township, spend the next five years cultivating the plot while living on it, and then they would be entitled to receive a land deed.

A SAILOR OF LAKES

As Byron traveled back east, he got as far as Erie, Pennsylvania, before the urge to be back on water beckoned to him. He easily found employment in the service of Hon. William Lawrence Scott, the owner of a fleet of steamships on the Great Lakes.

Steamship lines on the Great Lakes were established by the railroads in the late 1850s. The vessels serviced traveling passengers and freight from a railhead on one side of the lake, sailing them across the lake to a railhead on the other side of the lake, so they could continue their journey by rail. The vessels carried passengers in staterooms on the top floors and packaged freight below.

In 1869, the compound engine was introduced into the screw-propelled steamships, which pushed the steam through the engine twice, which resulted in the vessels operating the steamship lines to move through the lakes with greater efficiency. Byron navigated Scott’s vessels on the Great Lakes for the next few years as first mate.

Byron was influenced by his relationship with Scott, who was a prosperous businessman who engaged in shipping, coal mining, and railroads. Byron returned to Little Falls in the early 1870s, relinquishing his life as a seaman on the water to see what he could do with his hands as a landsman on land.

Byron, at the age of thirty, married Anna Buckley, the nineteen-year-old daughter of William Buckley, a fellow Irishman, at Little Falls on the 9th of June in 1874. Before she wed, Anna had worked in a woolen mill since the age of fourteen. Anna was known to her family as Annie, the Irish nickname version of her name.

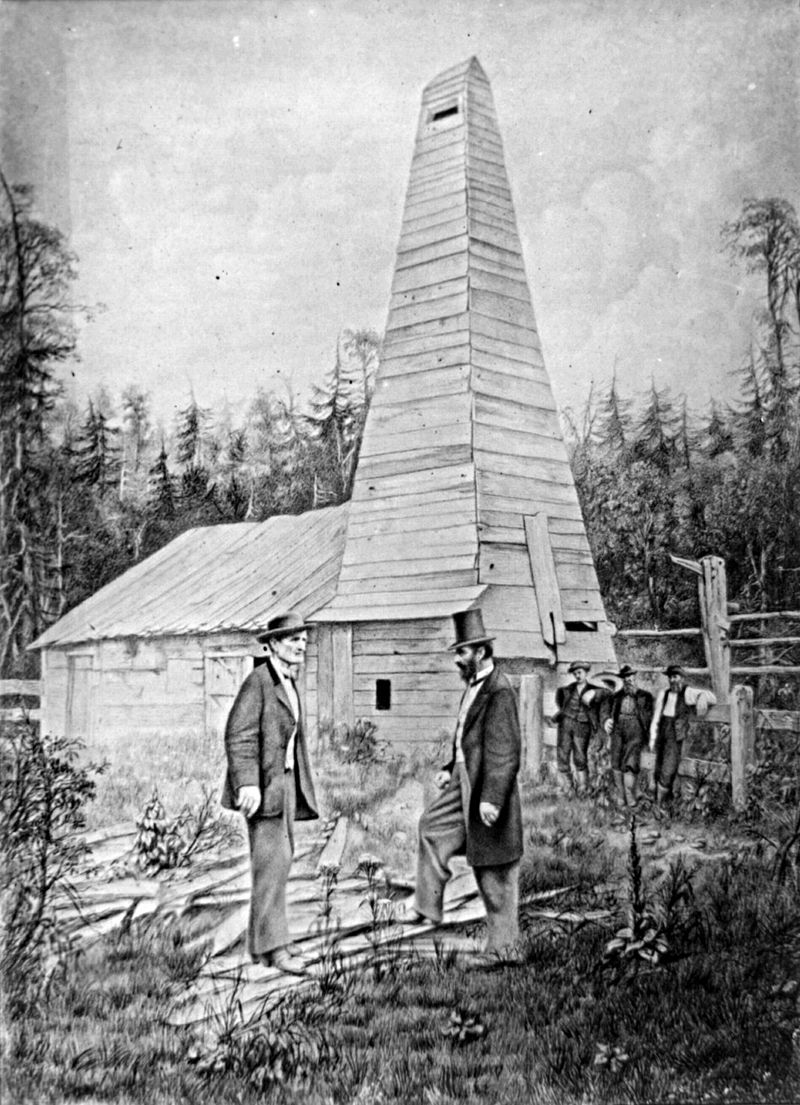

OIL FIELDS OF PENNSYLVANIA

The oil rush in America first took place in Titusville, Pennsylvania, where the first commercial oil well was drilled in 1859. The oil industry was well established in Pennsylvania by the mid-1870s when Byron took an interest in the oil fields. He traveled to the petroleum center of Pithole, Pennsylvania, just south of Titusville in 1876. He spent a short time in Pithole learning the oil well trade, when he then attached himself to a wagon train heading to the Western Plains. On this wagon train, Byron made it as far west as the plains of Nebraska. Not finding what he was seeking for the second time in the West, he was soon on his way back to the East.

The Drake Oil Well – Was the First Oil Well Drilled in 1859 | Edwin Drake, Man in the Top Hat

After returning to Little Falls yet again, Byron then decided to head to Bradford, Pennsylvania, where he worked in the oil fields as a driller. Bradford, a city that became well known in the 1930s for the invention of the Zippo lighter, is located a couple of miles from the New York border, fifty miles northeast of Pithole, Pennsylvania. After a short time, he then embarked in the oil business as a contractor. After several years of contracting, Byron sought out investors to secure several tracts of land nearby within an area that was known as the Bingham Estate. The estate encompassed over one million acres of land in northern Pennsylvania. It was owned by former Senator William Bingham, who was considered the richest person in the United States in 1780 when the estate was first formed.

CHARLES P. BYRON STRIKES OIL

The tracts of land chosen by Byron in the Bingham Estate were considered a “barren waste of lands” and were sold by the sheriff for unpaid taxes. As soon as the land tracts were secured, Byron began drilling, with a premonition that the oil fields would yield a profit. After drilling for some time, it was reported in the Elmira Gazette of Elmira, New York on the 17th of March in 1883, that Charles P. Byron unexpectedly hit a gusher. It was one of the largest oil wells struck within ten years in Bradford’s oil history, raising the prices for acreage in the Bingham Estate to “gilt edge prices.” The oil pool opened by Byron was estimated to be one mile in width and three miles in length and was struck at a depth of 2,170 feet. The oil well flowed at two hundred and fifty barrels a day, making Charles P. Byron a wealthy man.

ANOTHER LITTLE FALLS OIL STORY

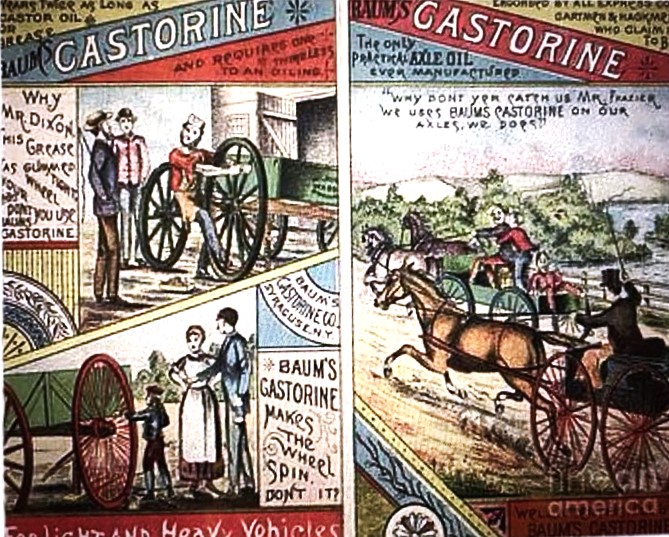

Similar to Byron, another Little Falls native, Benjamin Ward Baum, found financial success in the oil business in 1860. His son, L. Frank Baum, author of “The Wizard of Oz,” was also in the business for a time around 1883. That business, the Baum Castorine Company, is still in existence today in Rome, New York.

Old Advertisement Ephemera For Baum’s Castorine c.1884

THE MOURNING OF CHARLES P. BYRON

Byron’s death came quietly on the 13th of September in 1912, after suffering for three long years from cancer of the larynx. He died at his home in Bradford, Pennsylvania, in the city where he made his home for the last thirty years of his life, in a modest house considering his wealth, at 111 Congress Street.

Byron also owned a house here in Little Falls at 4 Dale Place at the time of his death. He purchased land lots #110 and #112 in 1906 for $3,100. from Lucey H. Clancey and had a house built there soon after. His daughter Lucy Alma Byron inherited the property in 1912, retaining it until 1922 when she then transferred the land deed as a gift to her aunt Maria O’Byron Lally. Before owning this property, Byron had owned a house at 38 Petrie Street, that has since been razed. Over the years, he had made frequent trips by train and in his touring automobile to Little Falls, visiting relatives and lifelong friends.

Throughout his years in Bradford, Byron maintained an interest in his oil and gas businesses, which he had invested wisely in, such as seeking new fields to develop for oil with securing 7,000 acres in Kentucky in 1895 of good oil, coal, and timberland. Amongst other investments, Byron also invested in 76 wells on 1,500 acres in Indiana, selling it at a fine profit in 1900. By the time of his death, he had purchased most of the investor’s shares within the Bingham Estate project of 1883, personally owning many of the oil wells. Also, upon his death, he held the position of president for the Smethport Gas Company.

According to his obituary, Charles P. Byron was known “… as a magnetic and shrewd businessman… a prominent man of affairs within the community …helpful to many people whom he regarded as deserving of assistance …was unassuming, straightforward, and outspoken …honorable and honest …and a remarkable man that accomplished much in his days.”

Byron was of the Catholic faith, being one of three people to fund the building of St. Ann’s Church in Mt. Alton, Pennsylvania in 1884. He also attended St. Bernard’s Church in Bradford, where he made large financial contributions, along with donating the bells that resound daily in Bradford. Byron had been a Democrat in politics and was a delegate for the state of Pennsylvania in 1888. He was also a standing member of the Associate Veterans of Farragut’s Fleet and a member of Bradford’s Knights of Columbus.

THE BYRON WILLS

Byron’s immediate family in Bradford, PA, and his extended family members in Little Falls, were separated by miles, but were close at heart, which was demonstrated in Byron’s will. He left $20,000 to be invested with the Buffalo, Bellevue, & Lancaster Fraction Company for the care of his sister Bridget O’Byron Clancy, and her daughter Lucy Clancy, a retired teacher of the Jefferson Street School at Little Falls. Bridget and Lucy relocated to Bradford, Pennsylvania when Byron first became ill. They were to receive $1,000. annually for living maintenance and were given life use of a house at 54 Jefferson Street in Bradford, Pennsylvania. The remainder of Byron’s estate was $153,311.50, which would be equivalent to that of $5,600,000. today. This sum was to be divided equally between his son and daughter, each receiving one-third of their inheritance at the time of Byron’s death. Another one-third disbursement of their inheritance was to be given to them five years after the death of Byron, with the final one-third disbursement of their inheritance to be given to them ten years after the death of Byron.

The family bond was also demonstrated in the will of Byron’s son Thomas, whose horrific death came at the age of thirty-five on the 27th of August in 1913. Thomas’ death was the result of his roadster losing a wheel while he was speeding in the automobile on a roadway known as “Laurel Hill.” The automobile flipped over onto its top, crushing Thomas underneath. A female companion accompanying him was thrown clear of the automobile, only receiving slight scrapes and minor bruising. The accident took place four miles from the village of St. Mary’s, Pennsylvania, as he was returning to Bradford after spending the day in the oil fields. Thomas left the sum of $2,000. to each of his six cousins residing in Little Falls and the rest of his estate was left to his sister Lucy Alma Byron.

THE INTERNMENT OF BYRON

Byron’s remains were transported by train to Little Falls, for his burial to be held in the place that he called home. A mass of Christian burial was held for him at St. Mary’s Church, at 9:30 A.M. on the morning of the 16th of September in 1912. Byron was interred in the Old Saint Mary’s Cemetery in the Byron family plot, Lot K-1 following the funeral mass.

Charles P. Byron lies in a perpetual sleep beside his wife Annie, who had died at the age of forty (1855-1895); his daughter Nellie, who only lived for eight short years (1873-1882); his son Thomas, a graduate of Columbia University, who worked as a news correspondent in New York City and was a prolific writer who authored at least thirty-eight short stories for a variety of magazine publications (1878-1913); his son Willie, who died at birth (1881-1881); his daughter Lucy Alma Byron Collins, who was born at Little Falls and died at the age of eighty-nine (1882-1971); and his oil producer son-in-law, Burt Harrison Collins who married Lucy Alma on the 22nd of June in 1915, with them making their home between Bradford, Pennsylvania and Tulsa, Oklahoma. He died at the age of fifty-three during appendix surgery (1879-1932).

Thos O’Bryon, known as Thomas O’Byron, the father of Charles, is also buried in Old Saint Mary’s Cemetery (1808-1875), with his will listing Charles, Maria O’Bryon Lally, Bridget O’Byron Clancey, Margaret O’Byron Chester, and Marcus O’Byron as his children.

THE BYRON MONUMENT

The Byron monument stands at a height of thirteen feet and was erected in the Old St Mary’s Cemetery one year before Byron’s death. It took five teams of horses to convey the twenty-ton limestone structure up the steep hillside and was put into place by William E Hennesy during the first week of May in 1911.

The Byron monument is carved in the cottage design, with a large, raised anchor adorning its face that signifies that Byron was a United States Naval Veteran. It also has an epitaph inscribed on a bronze plaque, attached below the anchor, which commemorates his military accomplishments with highly earned praise.

Charles P. Byron’s epitaph reads as:

Born in Ireland in 1844. Entered the United States Navy in May 1861. Served on the Strs. Penguin and Oneida. Participated in the Battle of New Orleans onboard the Oneida, the Fourth ship of the First Division in the line of battle under Admiral Farragut. Assisted in the capture of Forts Jackson and St Philip, the fortified defenses of the Lower Mississippi, and the City of New Orleans. Took part in the Battle of Vicksburg. Received with his shipmates the congratulations of the Navy Department, the Government, and the Country for Courage and Daring in letters from Washington dated May 10th, 1862. Took part in the engagements on the Potomac River and at Port Royal on Nov. 7th, 1861. Honorably Discharged on July 18, 1863.

A PEACEFUL REST

The life story of Charles P. Byron comes to an end as one retreats from the summit of Old St. Mary’s Cemetery and leaves the solemn gravesite of the Byron family behind. One may contemplate as one follows the meandering roadway as it descends downhill, that Byron’s life was a life well lived and a life in which a lesson could be learned.

As one exits the Old Saint Mary’s Cemetery, one may just whisper…Rest in peace, Charles.

Written by Darlene Smith, under the guidance of Louis W. Baum, Jr., both members of the Little Falls Historical Society.

14 North Ann Street | First Hospital at Little Falls, New York | Established 1893 | Dr. Eveleth holding is the horse's reins.

14 North Ann Street | First Hospital at Little Falls, New York | Established 1893 | Dr. Eveleth holding is the horse's reins.