The Palatine Germans in Search of a Land to Call Home

January 17, 2022 marks the 300th anniversary of the Burnetsfield Patent.

The earliest European settlers in the Mohawk Valley came from what is now southwest Germany. Under near constant threat of destruction, whether from multiple wars, invasions, or the plague, in the near hundred years leading up to the 18th century, the southwest German population experienced extreme hardship. In some cases, entire towns and villages were wiped out. Commercial crops in the vineyards either failed or were destroyed. Invading French armies added to the hardship by burdening residents with housing and supporting soldiers albeit with scant family resources forcing many German homeowners to flee.

In an effort to increase local populations, principalities began making religious concessions in the mid-1600s to various denominations in an effort to encourage settlement in the Palatinate. Menonite, Catholic, Lutheran and Jewish people began migrating to the area. This served the principalities well because more people meant more labor to work which led to increases in tax revenue. With so many people on the move, southwest Germany became very diverse with migration becoming a way of life in the region.

The severely cold winter of 1709, at the time referred to as “The Great Frost,” added to the already hard life throughout the Palatinate. The extreme cold destroyed German vineyards and crops alike. With the coming spring, thousands living in southwest Germany began petitioning the nobility to leave the area in search of a better life where crops could grow and lands would provide for families. Some estimates indicate that more than 15,000 Germans began leaving their homeland at this time. They left with the hope of feeding their families. They left in search of the free lands described in pamphlets and books telling of the fertile farmland in America. These pamphlets had been circulating for some time with the encouragement and backing of Queen Anne of Britain. Penn, Pastorius, Faulkner and Kocherthal all authored publications describing the British colonies in North America. In particular, Joshua Kocherthal’s short book in its third and fourth editions, written in German and intended to be either read or spoken, made it easy to be disseminated throughout the German population.

It wasn’t long before many Germans decided to travel to America. They had been struggling for quite some time on their lands and wanted more for themselves and their families. What was before them was a long and arduous journey. Most of the migrating Germans slowly sailed up the Rhine on to Rotterdam for passage to England. Once they arrived in London, the Germans were faced with yet more harsh conditions where their very survival depended on the mercy of the British people and government. Some of the Germans that arrived in England decided to end their migration and settle there. Others went on to Ireland. Still there were many who were ready to make the long voyage across the Atlantic to America to acquire lands for homes and farms. One group of about 3,000 Palatine Germans looking for a better life finally set sail to America in January of 1710, approximately a year after they left their homes in Germany. There were so many passengers making the overseas journey that the fleet required ten ships.

One of the passengers, Ulrich Simmendinger, would later take a census of the Palatine Germans who traveled with him. Of the 3,000 Palatines that traveled with Simmendinger, 480 did not survive the six-month journey across the Atlantic. Interestingly, before Simmendinger left America in 1717 he traveled to all of the German settlements in New York and New Jersey to learn about what became of his travel companions and their families.

After finally making the six-month journey to New York in 1710, the Palatine Germans were then quarantined for five months before being sent to Livingston Manor where they would live in the West Camp on the Hudson River and work for the Naval Stores project. From the British Calendar of Treasury Books Volume 24, 1710:

“Additional instructions under the Queen’s sign manual, dated “at our Court at St. James’s,” to Robert Hunter, Captain General and Governor in Chief of the Province of New York, concerning employing Palatines in making pitch and tar: the Commissioners of Trade and Plantations having by their representation of Dec. 5 last laid before her Majesty a scheme for settling about 3,000 Palatines at New York and for employing them in the production of naval stores in that Province, which the Queen is willing to promote as being good and advantageous. The said Governor is hereby to put the scheme as follows duly into execution upon his arrival at New York.”

The project’s goal was to produce pitch and tar for Britain’s vast navy, but ultimately, the Naval Stores project cost far too much and without sufficient yields thereby failing in its objectives. It was eventually abandoned under the leadership of Governor Hunter who lost a lot of his own money investing in the project. This failed project was a devastating blow to then Governor Hunter. The Palatines, however, lost years living in the camps with little hope of receiving their promised land. After the project’s failure, some of the Palatine Germans settled on the Hudson River, while others still held out hope that they would acquire land for farms of their own in New York.

Queen Anne’s Promised Land

In 1720, England’s Board of Trade made recommendations to New York’s new governor, William Burnet, to establish lands for the German Palatines, “for such of [the Palatines], as desire to remove to proper places.” By January 17, 1722, and after repeated petitions to Her Majesty’s government, the Palatine Germans could finally see their hopes and dreams of their own land to call home coming to fruition with tracts of land on both sides of the Mohawk River with the easternmost boundaries at the Little Falls. Historian Nathaniel Benton details,

“It recites that “whereas our loving subjects, John Joost Petri and Coenradt Rickert, in behalf of themselves and other distressed Palatines, by their humble petition presented the 17th day of January, 1722, to our trusty and well beloved William Burnet, Esq., Captain General and Governor-in-chief of the province of New York, in council have set forth that in “accordance with the governor’s license they had purchased” of the native Indians in the Mohawks country” the tract of land on both sides of the “Mohawks river” commencing at the “first carrying place [Little Falls], being the eastermost bounds called by the natives Astourogon, running along on both sides of the said river westerly unto a place called Ganondagaraon, or the upper end of it,” being ” about twenty-four English miles along on both sides of the said river. ‘ The Indian deed is dated July 9, 1722. That the council advised the governor to “grant to each of the said persons, man, woman and child, as are desirous to settle within the limits of the said tract of land the quantity of 100 acres.”

In documents dated November 21, 1722, Governor Burnet wrote to the British Council of Trade and Plantations about the Palatine Germans,

“I have given them leave to purchase land of the Indians, between ye present English Settlements near Fort Hunter and part of Canada, on a Creek called Canada Creek, where they will be still more immediately a barrier against the sudden incursions of the French, who made this their road when they last attacked and burn’d ye frontier town called Schenectady.”

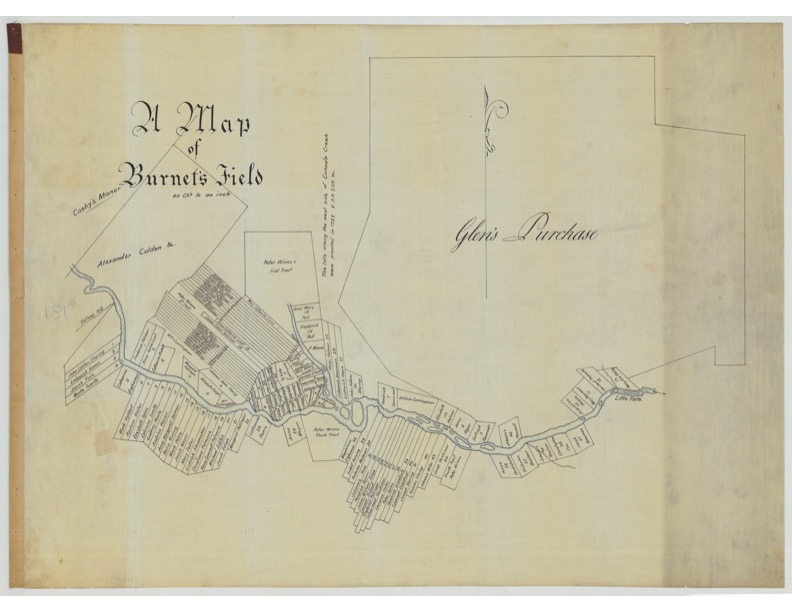

Map of Burnet’s Field

A Land to Call Home

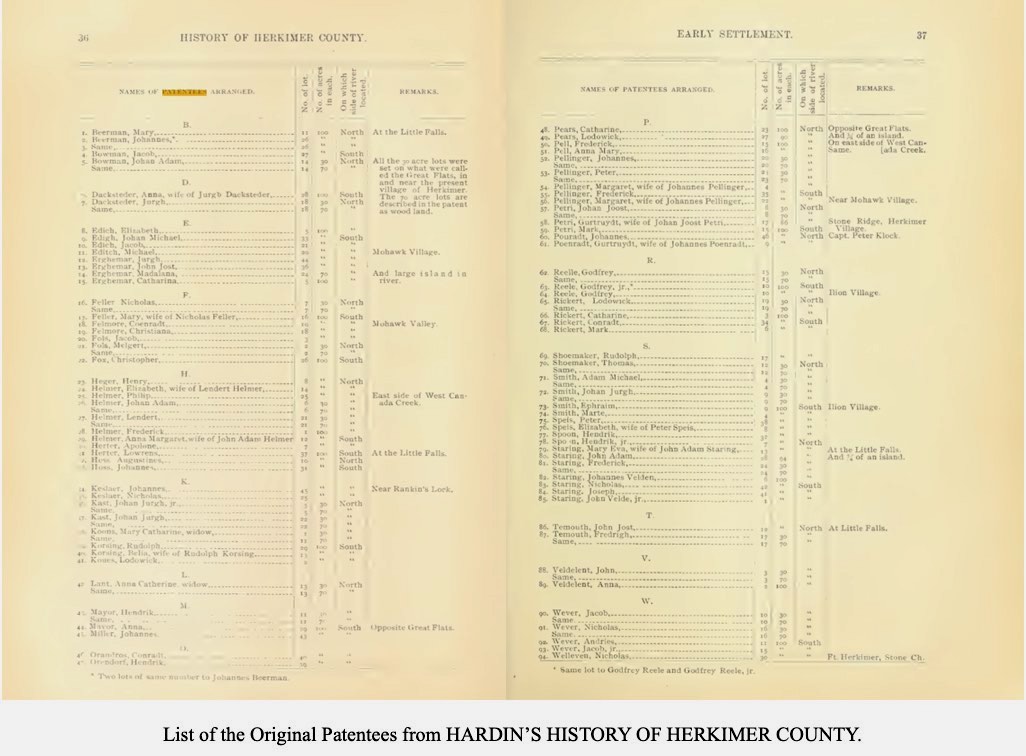

Looking at the Mohawk River Valley, the British Government decided to settle the Palatine Germans as far west as was practical. Burnet’s acknowledgement that the land purchase created a “barrier” on the western frontier it becomes clear how dangerous the land grant’s area was. On April 30, 1725, Governor Burnet signed the land grant, known as the Burnetsfield Patent, granting lots to 94 patentees that would build homes and farms for their families in one of the most dangerous areas in these British colonies.

Some of the land was divided into long narrow parcels to give many of the patentees access to land that was flat and suitable for farming, while also giving them access to woodlands for timber. The way the tracts were parceled was in fact very similar to the way lands were allocated in Germany including the boundary along the river. Even at the edge of the frontier, this land would provide the rich soil and enough timber resources to build long-awaited homes for the Palatine Germans.

Those Palatine Germans that were granted parcels in the Burnetsfield Patent of 1725 established homes, farms, and communities throughout the central Mohawk Valley. An insight into their lives is given through this translated letter dated July 10, 1749 from Lot 43 patentee Johannes Müller and his wife, Anna Maria, to their family back in Germany.

“Our greetings first! Dearest brother and all friends together with their families!

Since I Anna Maria from Germany have been in America, I could never find the opportunity to report a few things about my life and situation. But since a good Palatine friend, Stephen Franck by name, a neighbor of ours, is traveling to the Palatinate and has some business in your area, I could not hesitate to look up you friends to learn how you are doing. Let you know that we have arrived in 1710 in New York after a long and troublesome journey, and then, during harvest time, my husband died after a short illness, being well at noon and dead in the evening. The infant boy born to us in Germany, Heinrich Hager by name, has married here and has 11 living children. I have remarried in 1711. My husband, Johannes Muller by name, still living by the grace of God, comes from Rutershausen, district office of Ebersbach, by whom in peaceful matrimony together we had 5 sons and 3 daughters, which the Lord up to this time has kept alive. Of them, 4 sons and 2 daughters are married.

Also, I wish to report that, even though the move to and the start in this country was hard, God blessed us nevertheless. He has given us our own land, bread, cattle and food so we may live, and we cannot be grateful enough to the Lord. We have no desire to return into your forsaken Egypt; but rather would that you could be with us. However, nobody can be told what to do, for the journey is very troublesome and subject to many discomforts; and life and death are not very far apart from each other.

I have learned that the princely house of Nassau has died out except Nassau-Ditz. I would like to find out from you, dearest brother-in-law, who rules over the principality, and whether things are still as rough as they were then. As far as I am concerned, we are, compared to the taxes in Germany, a free country. We pay taxes once a year. These taxes are so minimal that some spend more money for drinks in one evening when going to the pub. What the farmer farms is his own. There are no tithes, no tariffs; hunting and fishing are free, and our soil is fertile and everything grows. I have 100 acres from the crown and bought another 100 acres.”

This poignant correspondence illustrates the hardships the Palatine Germans faced while shedding light on the new life they created in the midst of these hardships. They worked the land along the Mohawk River contributing greatly to one of the “richest farming regions in the northern colonies.” This land was everything the Germans had hoped for.

Less than ten years after Anna Maria and Johannes’ letter was written in the fall of 1757, the Burnetsfield patentees north of the Mohawk River were raided by the French with devastating consequences. Some of the Oneidas tried warning them about the impending attack, but the patentees on the north side did not believe there was any reason for alarm. The Oneida leader, Canaghquayeeson details in his narrative of the time that the Germans “paid not the least regard to what I told them; and laughed at me, slapping their hands on their buttocks.” The Germans had worked very hard to build trading relationships with the tribes and did their best to remain politically neutral between France and England. They believed themselves to be farmers and traders so when some of the tribes came with warnings they didn’t see any threat. Some reports of the time describe how when some of the Oneidas discovered that the Germans were to be targeted in the raids, at least a hundred turned away. Unfortunately, however, with no protection, the attack still resulted in 8 deaths and over 100 people taken as prisoners to Canada. Homes, farms, and livestock all were completely destroyed.

When threats of raids came the following spring, the south side patentees took the warnings seriously and narrowly escaped finding refuge in Fort Herkimer. Any threats to the lands they now called home were heeded with whatever action necessary to protect their lives, homes and communities. After enduring generations of hardship in the Palatinate and journeying thousands of miles in search of land so their families could thrive, they had become inexplicably tied to the land. And they loved this land. It was their promised land where the “soil is fertile and everything grows.”

Ginny Rogers is a member of the Little Falls Historical Society.