LOCAL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY REFLECTED STATE AND NATIONAL EVENTS

AFRICAN AMERICAN BURIAL GROUND IN CHURCH STREET CEMETERY

The primary purpose of this piece of writing is to chronicle a history of African American presence in Little Falls from the time of slavery up to the 2015 dedication of a monument in Little Falls Church Street Cemetery recognizing what was once known as the “Colored Burial Ground.” Related New York State and national events are also included to help provide historical context.

The final portion of this piece provides a number of short biographies of individuals buried in the African American section of Church Street Cemetery.

Slavery, runaway slaves, Black Civil War soldiers, the Black AME Zion Church, a Black community with Black entrepreneurs, a segregated burial ground in a public cemetery, Little Falls has had an African American presence for at least two hundred and fifty years.

THE GROWTH AND HORRORS OF SLAVERY

Slavery in America began around 1619 in Jamestown, the first British southern colony. These Virginians were near starvation and desperate for labor to grow corn for subsistence and tobacco for export. Black slaves would provide needed labor. Lifelong hereditary bondage became the institutional norm for those unfortunate individuals and families. Slaves were considered property or chattel; slavery became formalized with the passage of southern slave codes.

Most slaves arrived by boat via the “triangular trade” between Europe, the west coast of Africa, and the West Indies and then onto southern American ports. Dark skin equated to inferiority, contempt, and oppression; racism and segregation followed. Slavery grew as the southern plantation system grew. By 1763, there were 170,000 slaves in Virginia alone, about half its population. Slaves generated southern wealth by toiling in the cotton fields and in southern mansions as domestics; extreme violence and brutality became a normal means of controlling the Black slave workforce.

An unfortunate reality of early American history is that many of our Founding Fathers, including George Washington (around 120 slaves), Thomas Jefferson (over 600 slaves), and James Madison (around fifty slaves), owned slaves. John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, owned many slaves at his Hudson Valley estate, as did Revolutionary War hero Philip Schuyler.

Miscegenation was often the byproduct of slavery as it was most common for slave masters to “take liberty” with their female slaves. It was not at all unusual to see slaves who physically resembled their plantation owners, something that was obvious but not talked about by visitors. The history of the Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hennings long term “relationship” provides ample evidence of such miscegenation.

Neil Young’s seminal song SOUTHERN MAN is a musical account of this grim reality.

This local historical account of Black history in Little Falls must begin with General Nicholas Herkimer and his ownership of slaves; this “free labor” was likely used by Herkimer, both to construct his stately home and to portage boats around the Little Falls rapids. Records indicate that Herkimer once possessed as many as thirty-three slaves. The 1790 census showed that Herkimer’s household still had nine slaves. Thus, slave labor helped fuel one of the first commercial enterprises in Little Falls; slavery generated early American wealth in both the north and the south. Herkimer’s wealthy neighbors also owned slaves.

England was central to the international slave trade. It was in England’s North American colonies that lifelong hereditary bondage was institutionalized, the slaves themselves could never legally gain their freedom, and their children were born into slavery under the same legal status. Theirs was a brutal existence reinforced by the perceived need to keep slaves ignorant and uneducated to the point of forbidding them from learning to read or write.

In 1781, the New York legislature voted to manumit (free) slaves who had fought in the Revolution, but it was not until1827 that slavery itself was outlawed in New York State. The 1830 census listed the Little Falls population at 1602, with a Black population of 85. The 1790 census listed early Little Falls resident John Porteous as owning two slaves.

The false concept of white supremacy emerged, in effect, “drawing the color line” between whites and Blacks to ensure slave subjugation and the separation of the races, in part, so that poor whites would feel superior to Black slaves. Otherwise, poor whites and slaves might combine against outnumbered southern cavalier plantation owners.

Floggings, smokings, branding, and other unimaginable horrors, were used to both increase slave work production and to discourage slaves from escaping. Slave revolts, such as the 1739 Stono Rebellion, the 1822 Denmark Vesey Conspiracy, and the 1831 Nat Turner Rebellion, provide proof that slavery existed without complete submission.

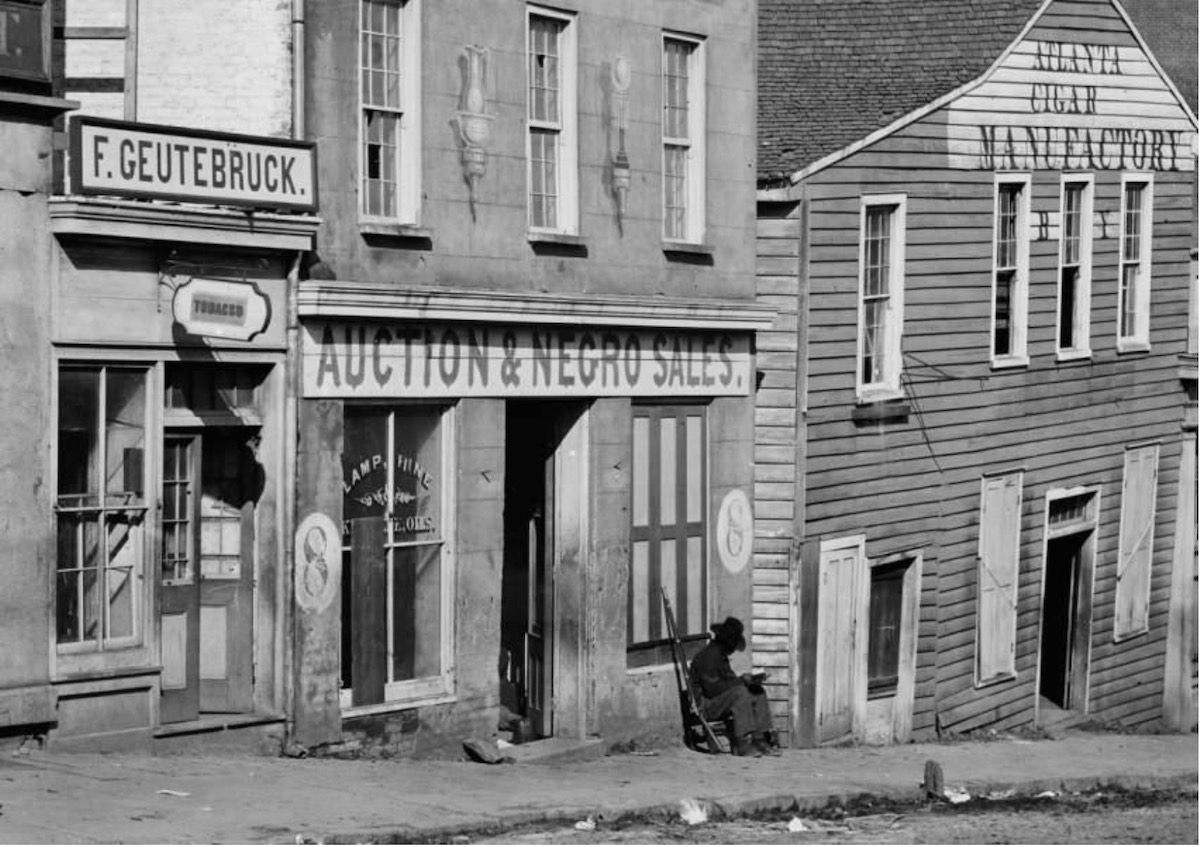

Former Slave Auction House, Whitehall Street, Atlanta, Georgia, November 1864.

The first organized abolitionist efforts to immediately free slaves began in the early-1830s in northern states. The first “old school” abolitionists opposed slavery on moral and religious grounds. New school abolitionists took more direct action. There is little historical evidence of abolition being a potent force in Little Falls, one is left to wonder how our ancestors felt about abolition.

SLAVERY AND ABOLITION IN NEW YORK STATE

The Dutch first introduced slavery in New Netherlands (later New York) in 1626 through the Dutch West India Company’s commercial enterprises. From there, slavery spread northward up the Hudson Valley, eventually as far as Fort Orange (later Albany.) Dutch American homesteads and the Dutch Reformed Church colluded to control slavery in the Hudson Valley. The British seized New York from the Dutch in 1664 after which time slavery continued to spread as white settlement spread north and west in New York.

By 1730, 42% of New York City residents owned at least one slave. What had begun as a haphazard practice under Dutch rule, slavery became institutionalized and codified under English rule. NYC began segregated burial practices in 1697, some 15,000 African Americans were interred in a burial ground in today’s lower Manhattan where a national monument now stands.

At the time of the American Revolution, Albany County, which then included what would later become Herkimer County, listed some 4,000 slaves. The 1790 census lists 14% of the New York State population as owning around 20,000 slaves, 6% of the state’s population.

Present day research challenges the myth that northern slavery was somehow more humane than southern plantation slavery. In fact, by the mid-18th century, there was an advanced system of violence and control that had much in common with the slave societies in the plantation south. Slavery generated wealth for the Hudson Valley elite for over 200 years.

There is an ongoing present day reckoning about the institution and nature of slavery at several historic sites in the Hudson Valley, including at the John Jay Homestead State Historic Site in Katonah. There is a similar reckoning taking place at present about the Schuyler – Van Rensselaer families’ 24,000-acre estate near Schuylerville. Philip Schuyler was a renowned Revolutionary War hero whose extended family owned over fifty slaves. Schuyler’s larger than life size statue had long graced a busy downtown Albany intersection near the state capitol until its recent removal. The idea of so honoring a former slaveowner offends modern sentiments.

The 1815 Herkimer County census reported that there were fifty-three slaves and forty-three slave owners. Additionally, the census also reported that the towns of Columbia, Fairfield, German Flats, Herkimer, and Schuyler were labelled “slave towns” while Frankfort, Litchfield, Newport, Norway, and Russia were labelled “free towns.” The town of Little Falls had not yet been organized.

Upon the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, abolitionist, women’s rights, and other social reform literature and ideas spread westward from port to port across what became known as the Burned Over District in western New York State. The Erie Canal thus served as “the internet of its day.”

Gerrit Smith was a wealthy abolitionist who helped free hundreds of slaves.

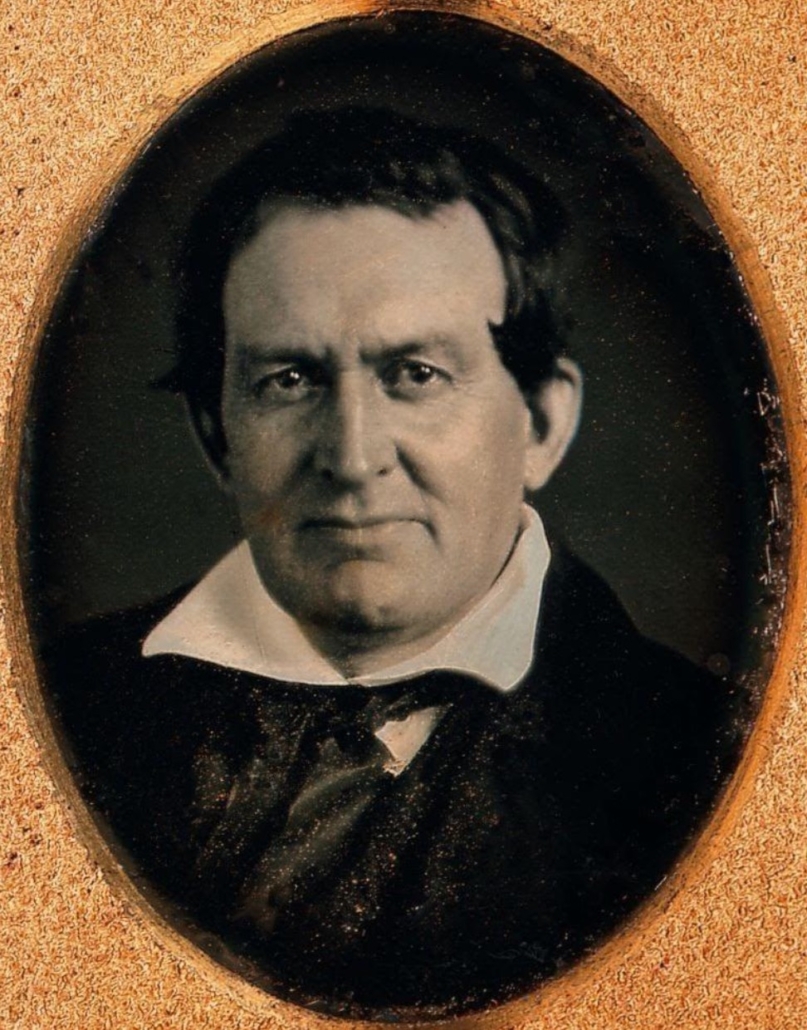

An interesting and influential New York abolitionist was Gerrit Smith. He helped establish the Upstate Anti-Slavery Society, and after an abolitionist meeting in Utica’s Bleeker Street Presbyterian Church was attacked by an anti-abolitionist mob, Smith began using his home in Peterboro as a base for upstate abolition efforts. In 1846, Smith donated 120,000 acres of land outside today’s Lake Placid to form the free Black colony of Timbuctoo. This became the base of operations for perhaps the most famous abolitionist of all, John Brown. Smith was driven by liberal ideals and empowered by his extensive wealth. He purchased the freedom of hundreds of slaves.

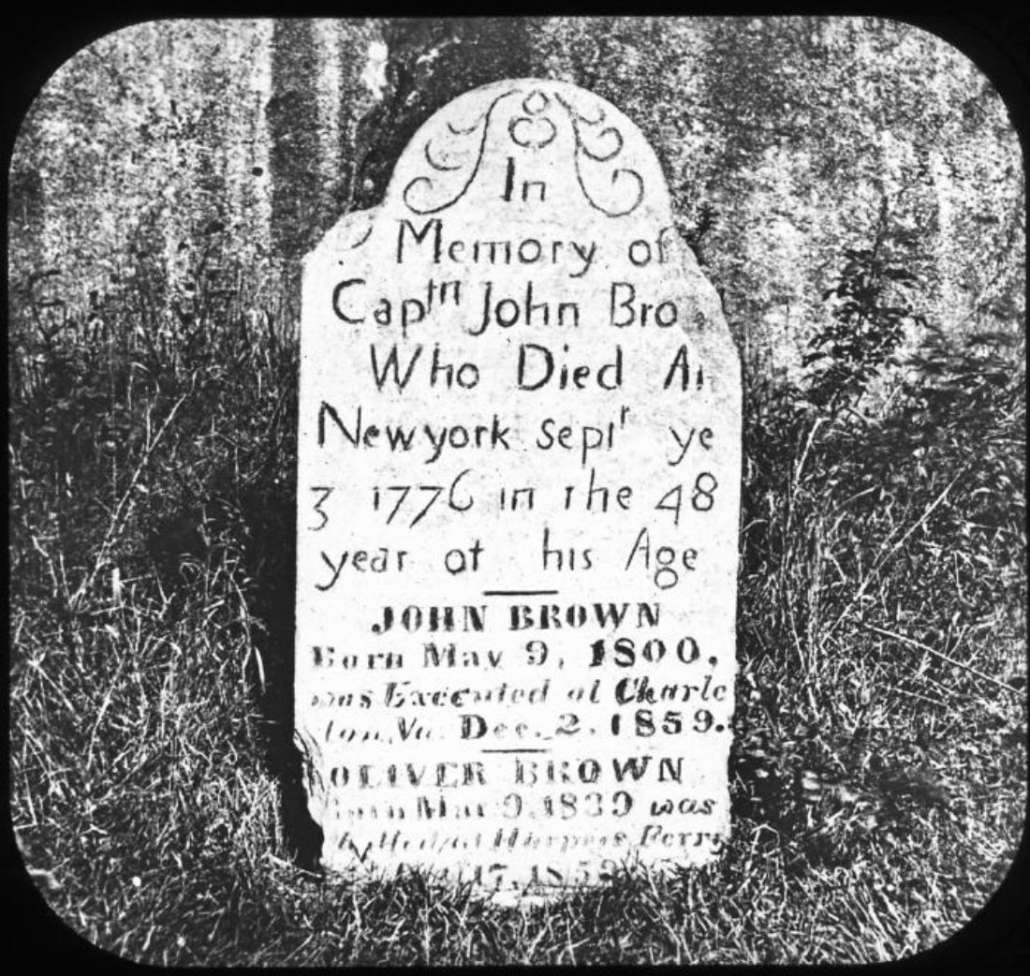

The Gerrit Smith Estate National Historic Landmark in Peterboro is a present-day museum dedicated to the study of abolition and women’s history. John Brown’s Farm historic site outside Lake Placid contains Brown’s remains which were returned there following his execution in Virginia for his role in raiding the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in 1859.

It has been said that Abraham Lincoln did with a pen (the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation) what John Brown attempted to do with the sword.

John Brown’s Grave located on John Brown’s Farm outside Lake Placid

SLAVERY AND THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

The Revolutionary War ended in 1783 and the United States Constitution was ratified in 1787. The document never mentions the word slavery, but the Founding Fathers left slavery legal, and every generation has since struggled with that legacy. The central paradox of pre-Civil War American history was the uneasy co-existence of slavery and democracy. The 1776 Declaration of Independence states that all men are created equal, but our Founding Fathers had no intention of including either persons of color or women in that calculation.

The 1857 Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sanford found that slaves were property, not citizens, and that residence in a free state, and later in a free territory, did not entitle Scott to sue for his freedom. White ownership of Black slaves was thus strengthened. Either directly or indirectly, the Dred Scott case was a cause of the Civil War.

Local reaction to the Dred Scott decision can in part be determined by an April 2, 1857 editorial in the MOHAWK COURIER. To quote: “This retrograde movement in favor of slavery, defies not only the sentiments of the Free States of the Union, but those of all civilized Nations on Earth.” Apparently, at least a portion of Little Falls residents were opposed to slavery and sympathetic to abolition.

EMERGENCE OF A LOCAL BLACK COMMUNITY

Chattel slavery and segregation existed in America for nearly two centuries before Little Falls was incorporated as a village in 1811. Prior to New York State’s abolition of slavery in 1827, Little Falls had an unknown number of both slaves and free Blacks. Free Blacks still resided here after 1827.

In 1840, the former slave Samuel Ringgold spoke at the Methodist Church in Little Falls urging for both emancipation and the elimination of property ownership requirements for voting. Around this same time, the fugitive slave Reverend Jermain Wesley Logeun visited the village and urged the construction of an AME Zion Church, half-way between Albany and Syracuse. He persuaded Enoch Moore to move to Little Falls to secure funds for building this church. For $450, this church, able to seat sixty persons, was constructed near the intersection of today’s Furnace and West Main Streets.

In 1843, noted Quaker abolitionist Abbey Kelly spoke at Washington Hall at the intersection of South Ann and Mill Streets in Little Falls and, on March 2, 1849, Reverend Samuel Orvis gave an anti-slavery lecture there entitled “The Evils of Slavery.”

Moore went on to become perhaps Little Falls’ most famous Black resident; the AME Zion Church was a likely stop on the Underground Railroad with both the Erie Canal and railroad close at hand. Moore was a likely local “conductor” on the Underground Railroad. The term Underground Railroad was of course a figure of speech, it was neither underground nor a railroad.

Zenas Brockett’s Freedom Home near Brockett’s Bridge (today’s Dolgeville) was an often- used Underground Railroad stop. The nearby old Military Road, connecting Johnstown with Sackett’s Harbor on Lake Ontario, was a much-used route to Canada for runaway slaves. The Union Church’s Brockett’s Bridge congregation was largely abolitionist and supportive of local Underground Railroad activity. The beautiful Underground Railroad mural in the Dolgeville post office captures much of this community history.

Statewide, AME Zion churches were urged to create a network of safehouses for fugitive slaves while also banding together to take direct political action against slavery.

Throughout the antebellum pre-Civil War period, the Little Falls Black community continued to grow, although some Black people died from cholera and consumption largely due to unsafe living conditions. The primary goals of this Black community were to abolish slavery and gain employment and voting rights for African Americans.

Ironically, Blacks were denied entry into certain professions, such as carpentry and masonry, requiring skills that many had gained while enslaved. Economic segregation both endured and prevailed.

In the pre-Civil War antebellum period, one is left to ponder public opinion in Little Falls regarding the institution of slavery itself and the likely presence of both fugitive slaves, former slaves, and free Blacks in the community. The federally enacted Compromise of 1850 included a strict fugitive slave law requiring all persons to aid and assist in the capture and return of runaway slaves. In other words, a person risked criminal prosecution if he / she was aware of the presence of a runaway slave and did not report that person to the authorities. How did our ancestors think about and act towards fugitive slaves? Few written records exist as aiding or harboring runaway slaves was criminal. Who would have kept a diary or written letters describing such “criminal” activity?

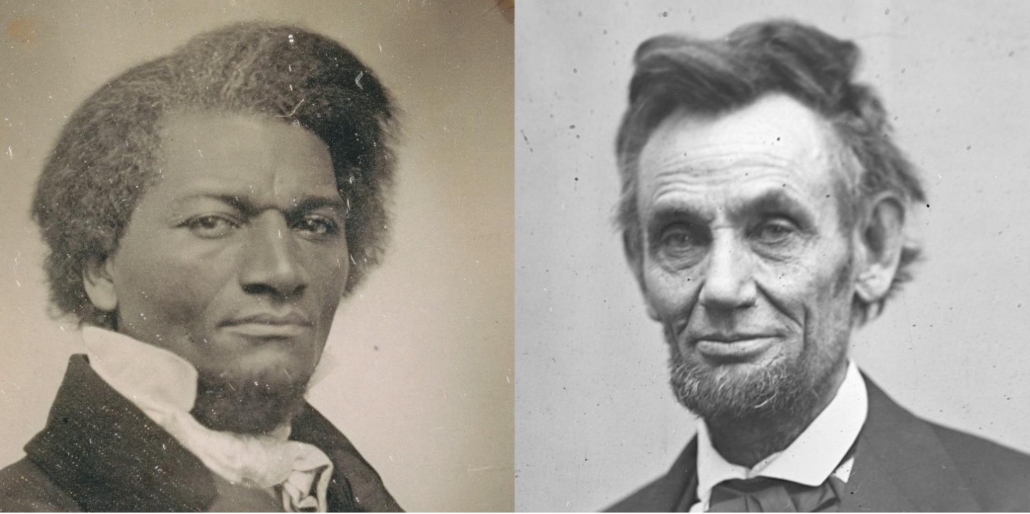

Black abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass reacted to this stronger fugitive slave provision by stating:

“The 1850 law has turned America into a hunting ground for men. Your lawmakers have commanded all good men to engage in this hellish sport.”

Escaped slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass • President Abraham Lincoln

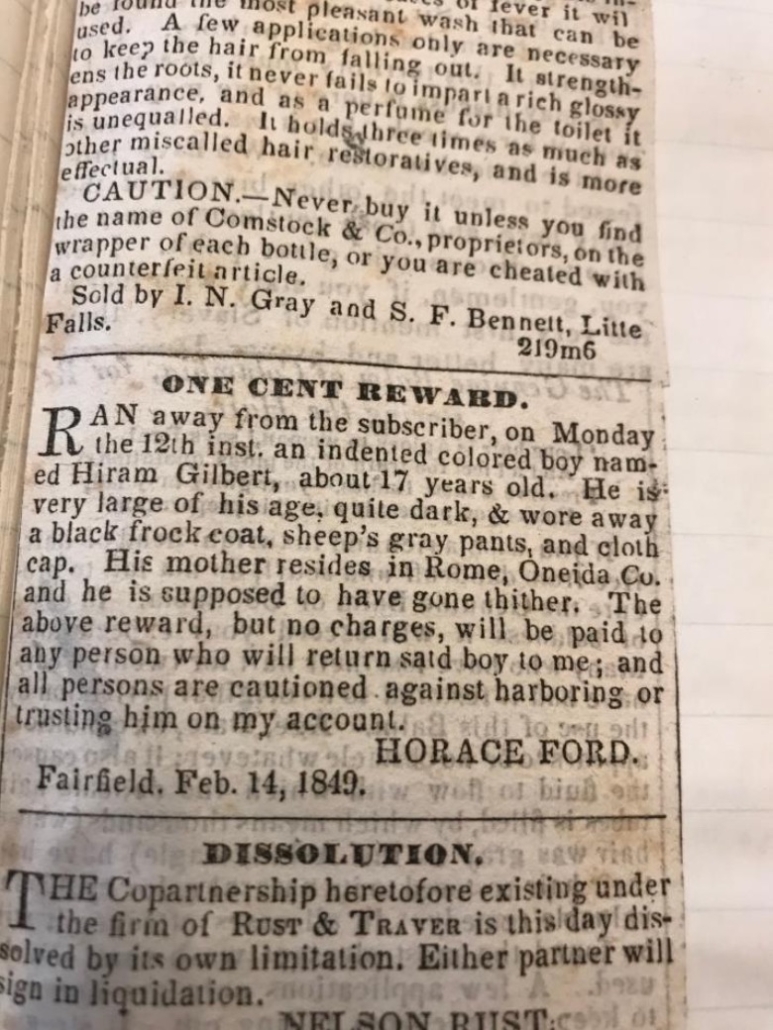

A February 1849 Little Falls newspaper ad read: “One Cent Reward – runaway, an indentured colored boy, Hiram Gilbert aged 17. The reward will be paid to any person who will return the boy to me. Horace Ford, Fairfield, NY.”

February 14, 1849 local newspaper ad.

THE CIVIL WAR AND ABRAHAM LINCOLN

By the time of the Civil War, there were around 3.9 million slaves in America, at least three million of them in the south. Either directly or indirectly, slavery was the cause of the Civil War.

The Civil War was by far the greatest cataclysm that ever visited the United States. During those four years of war – April 1861 to April 1865 – it is estimated that 625,000 Americans perished, about one in every fifty Americans alive at that time. That death toll is larger than the combined total of all other American conflicts from the Revolutionary War to the present day. There were twenty-five Civil War battles, most of which a majority of Americans have never heard of, where the casualty count exceeded that of the June 6, 1944, D-Day invasion during World War II.

Sadly, Little Falls contributed its share to the national death toll. Seventy men from our village and town never returned home, a number nearly equal to the Little Falls men lost in all of America’s other wars. Disease was the major cause, but the battlefield exacted its fair share. The majority of the fallen are buried far from home, many in unmarked graves.

Although the records are incomplete, a best estimate is that 565 men from Little Falls, volunteers all, served during the Civil War. To date, no man from Little Falls has been found who was conscripted (drafted) into the Union army.

As evidenced in letters and diaries, almost to a man, the only reason given for volunteering was to save the Union. Many men made it a point to state that they were not willing to risk their lives to free slaves and that their primary purpose was to put down the rebellion. (The contemporary title of the conflict was “The War of the Rebellion.”) Most northerners, having had no brush with slavery or slaves, did not understand what human bondage entailed. On one side, propaganda from the south detailed the benevolent aspects of slavery on African Americans, while on the other side, abolitionists graphically presented the horrors of “the peculiar institution.” However, after viewing the plight of African Americans in slave country, most Union soldiers added the end of slavery to the reasons that they were fighting.

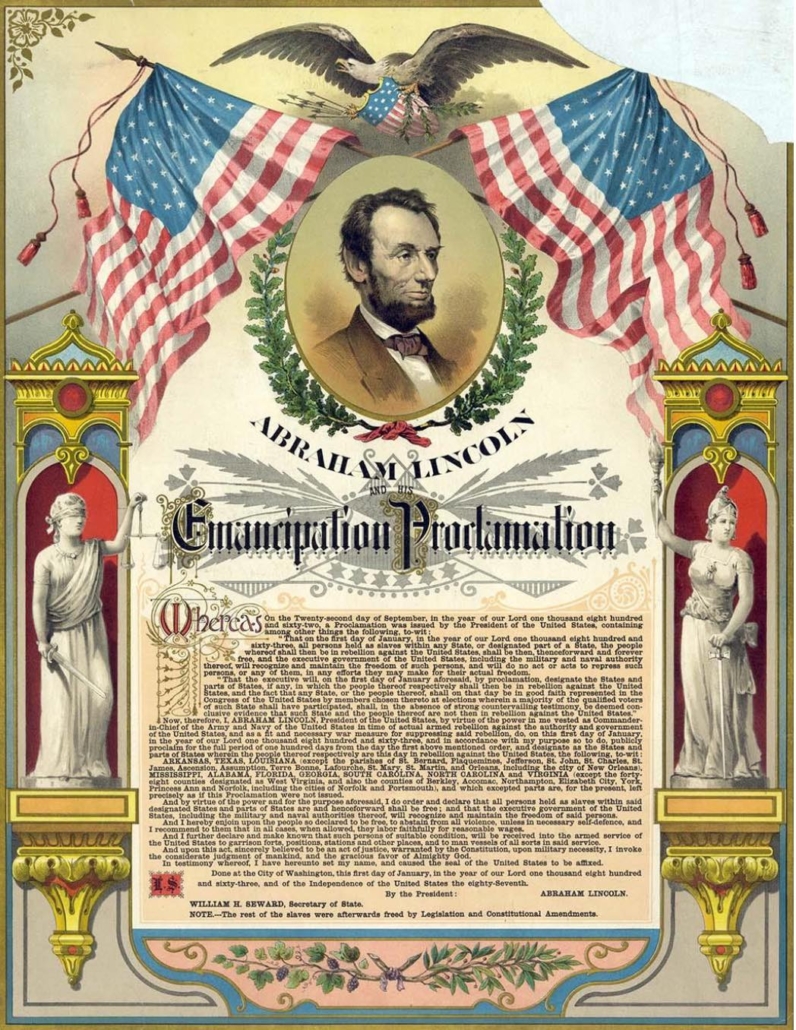

African Americans were not permitted to enlist in the Union Army or Navy during the first two years of the Civil War. Among the prevailing thoughts were that using Blacks as front-line soldiers would give the south a propaganda tool to show that the north did not really care about the lives of these men. There was also the belief that “docile” African Americans were incapable of surviving the rigors of combat or following orders and therefore would be slaughtered in battle as a result. Blacks, primarily runaways, had served the Union Army as teamsters, stevedores, cooks, and general laborers, but none had been handed a gun. The status of Blacks as non-combatants changed on January 1, 1863, with the enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation which, among other things, opened enlistment in the Union military forces to African Americans.

Time period poster of Emancipation Proclamation.

In the spring of 1863, Little Falls resident Enoch Moore was instrumental in raising forty-five recruits for the “Colored” 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, (famed in the movie “Glory”). Although newspaper accounts stated that these men were from the Mohawk Valley, records show that none of these men were from this area, the majority being from western New York or Albany. It is thought that Moore’s success in recruiting men from the western part of the state was a result of his once being the pastor of the Ithaca, N.Y. AME Zion Church and a station master on the Underground Railroad in that area.

The Shaw Memorial located in Boston Commons across from the Massachusetts State House.

Two African Americans from Little Falls, Horace Dygert and George Jackson, did fight during the Civil War. Dygert with the 20th U.S. “Colored” Infantry Regiment and Jackson with the 8th U.S. Artillery. Both survived the war, returned to Little Falls, and are buried in the “soldiers’” plot in Fairview Cemetery. Also buried in Fairview are York Cantwell and Benjamin Sears. Sears, a barber from Little Falls, served as a “servant” with the 117th New York and Cantwell, who came to Little Falls after the war, was in the 2nd U.S. “Colored” Light Artillery. Gravestones mark the resting places of both men.

Civil War Burial Section of Fairview Cemetery outside Little Falls.

As reported by The Herkimer County Journal, Reverend W. L. Tisdale, pastor of the Little Falls AME Zion Church, served the Union army as a non-combatant. Tisdale resigned from his post at the AME Zion in April 1864 and gained a position with the United States Christian Commission. In that role, Tisdale traveled into the war zone with the “boys in blue” ministering to the souls of African American troops and runaway slaves.

Also notable is the story of Addison Phillips, a runaway slave from Virginia, who stumbled into the camp of the 34th New York, the “Herkimer County Regiment”, which counted a large number of Little Falls men in its ranks. Addison stayed with the regiment, acting as a groom, cook, servant or whatever else was needed. When the 34th mustered out of service in June 1863, he was encouraged to come to Little Falls. After the war, he was rejoined here by his wife and children and moved into a home on King Street. During his time in Little Falls, he was a well-liked individual, known by all. Addison Phillips, his wife, and a son are buried in the African American section of Church Street Cemetery.

On April 15, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Like the rest of the nation, the news of Lincoln’s death stunned Little Falls residents. Black and white crepe paper adorned many businesses and homes and an uncomfortable silence settled over the village. Lincoln’s funeral train made a brief stop in Little Falls on April 26th. A huge crowd gathered at the depot and eight ladies dressed in black presented a wreath of woven wildflowers in the shape of a shield and cross to Colonel James Bowen. Bowen, a former resident of Little Falls, was one of the officers charged with guarding Lincoln’s remains. After the ladies and four prominent Little Falls men were allowed to pass through the funeral car, the train restarted on its way to Lincoln’s burial site in Springfield, Illinois.

A national day of “Humiliation and Prayer” for the death of Lincoln was observed on June 1, 1865. In Little Falls, the new pastor of the AME Zion Church, Reverend Humphreys, delivered the keynote sermon at the village’s Baptist Church before a packed house. The awful Civil War was over, but the mourning for the departed President and for all the of the village’s boys that would not be returning home again would never end.

The Herkimer County Journal reported on June 1, 1865: “Services – To-day having been designated as a day of Humiliation and Prayer for the death of President Lincoln, Union religious services will be held at the Baptist Church, where a sermon will be preached by Rev. Humphreys of the M.E. Church at 11 o’clock.” This notice was a reference to the AME Zion Church in Little Falls.

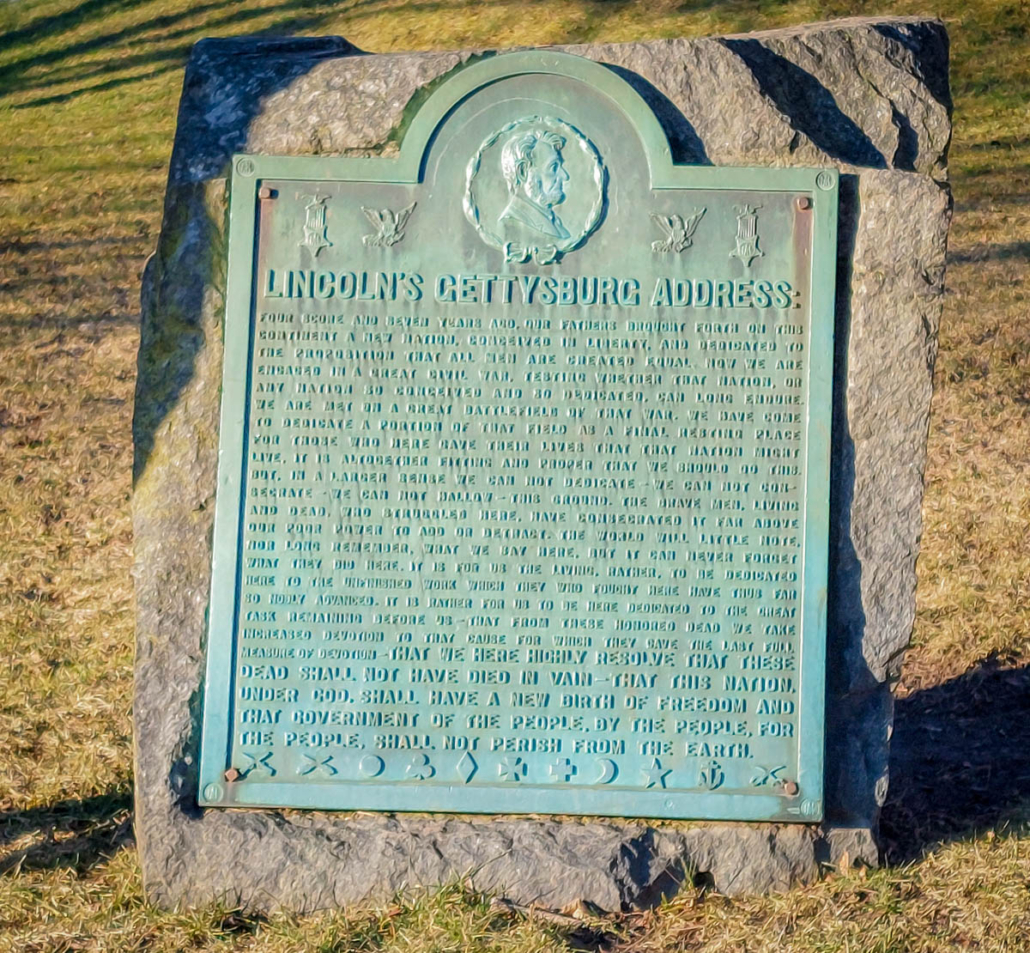

The Abraham Lincoln Gettysburg Address monument in the southeast corner of Ward Square is an impressive reminder of Lincoln’s great mid-Civil War action which transformed the whole purpose of that conflict.

Gettysburg Address monument.

RECONSTRUCTION AND THE RISE OF JIM CROW

Historian Howard Zinn refers to post-Civil War Black status as “emancipation without freedom.” Lincoln’s mid-Civil War 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, and the 1865 13th Amendment, may have officially abolished slavery, but the Civil War did not usher in anything resembling equality for Black Americans. Recovery from civil war left the north and south as very different regions economically and socially. Throughout the late-1800s, the north became ever more industrialized while the south remained mostly agricultural with the need for a huge workforce.

Unfortunately, most southern Blacks went from being pre-Civil War slaves to being post-Reconstruction, easily exploitable sharecroppers, or tenant farmers. To keep former slaves in such servitude, entrenched racism and institutional segregation became the norm. Jim Crow laws kept Blacks both mired in poverty and politically powerless. There was a lack of federal resolve to enforce the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, granting freedom, equal citizenship, and suffrage rights for Black Americans. The enactment of Jim Crow laws ensuring separation of the races soon followed. The Ku Klux Klan emerged during the 1870s to help keep Blacks fearful and “in their place.”

Locally, the 1870 local census showed Blacks employed as barbers, dyers, horse dealers, and gardeners. Little Falls was a somewhat multiracial community with whites and Blacks living side by side, mostly in the village’s first ward. An 1881 village directory showed at least ten Black households, mostly located near the first AME Zion Church on West Main Street.

A most interesting several days long “colored camp meeting” took place in Wilcox’s rural grove, likely near today’s Valley View Courts off East Monroe Street. A July 9, 1889 Evening Times article reported that the combination religious revival and social event was well-attended, mostly by white village residents. The principal speakers were Mrs. Lavender, a former slave from Virginia, the Reverend A. V. Dickson, and the Reverend James Mason from Ithaca, reputed to be one of the finest Black orators in the country. Spectators seemed to have been drawn as much by curiosity as religious conviction. The Jubilee Singers also performed. Over eight hundred spectators attended one of the days. Admission was reduced from twenty-five cents to fifteen cents on July 4. Vendors lined the roadways.

On September 27, 1889, the cornerstone was laid for the second African Methodist Episcopal AME Zion Church on West Main Street, there is no record of when the first AME Zion Church was built. The church became central to the lives of the Black community in Little Falls.

AME Church Steeple in foreground on W. Main Street, Little Falls

AME Church in foreground (enlarged).

The 1900 census showed Little Falls had a population of 10,381: 8436 native whites, 1875 foreign born, sixty-six “colored”, and four Chinese.

An April 23, 1903, newspaper article reported: the grand “colored” ball and cake walk was held this evening at the Cronkhite Opera House. This cakewalk featured couples from Utica, Syracuse, and other neighboring communities. Both whites and Blacks spectated from the balcony for this most spectacular annual event.

The game of base ball exploded onto the national scene in the years after the Civil War, (before the turn of the twentieth century the sport was titled with two words, as opposed to the modern-day name, “baseball.”) Before this time, the primary “sport” in the United States was horse racing; no real “team” sports existed. As the country’s economy began to boom and “leisure” time increased, the sport of base ball evolved from a game principally played by boys, called “rounders”, to the game we know today. When the work on the farm or factory was done, young men eagerly took up the bat and ball in their free time.

In Little Falls, much like the rest of the country, base ball became a passion. Every community throughout the Mohawk Valley fielded a team which carried their village’s banner. Fire companies, policemen, factories, service clubs, and even doctors and lawyers formed teams, and no clambake or family picnic was complete without a game of base ball.

The local African American community of Little Falls was no different and fielded a team in the 1880s and 1890s called the Rocktons (not to be confused with an all-white team of the same name.) Through contributions from local residents, enough money was raised to purchase uniforms and base ball equipment. Due to the dearth of available players – the Black population of Little Falls during this time being less than one hundred – the Rocktons often had to recruit players from as far away as Utica. The team that they fielded was good, very good.

Like most Little Falls teams, the Rocktons played their home games on Skinner’s Flats, a farm meadow above Furnace Street. Away games against all-white teams were quite common, with a post-game meal provided by the host being standard practice. After an 1887 game in Canajoharie in which the Rocktons prevailed in a shortened contest 33 to 5, both teams sat down to a “wine supper.”

Over the years, other African American teams came to Little Falls for ballgames. In 1870, “colored” teams from Johnstown and Utica played a “match game.” The Fearless Club of Utica bested the Wide Awakes of Johnstown 45 to 36. In the 1890s, the Fearless Nine from Utica would display their ball-hawking skills at Taylor Driving Park against the home team, the Baileys.

As the African American population of Little Falls declined as the century turned to the twentieth, so did the presence of Black base ball players. However, the athletic skills of African American ballplayers can still be viewed locally at Diamond Dawg, high school, and American Legion baseball games.

Little Falls and other northern white communities reacted with both fear and fascination to Black music and culture as more Blacks migrated northward from the segregated south. Jim Crow laws enforced southern institutional segregation and the ever-strengthening KKK provided intimidation and death. The south averaged around one hundred “social lynchings” of Black citizens per year in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Lynching victims had committed no crimes, such deaths were intended to “send a message” of intimidation.

Jazz great Billie Holiday’s dark 1939 song STRANGE FRUIT captures the horrors and terror of lynchings and white reaction to such events.

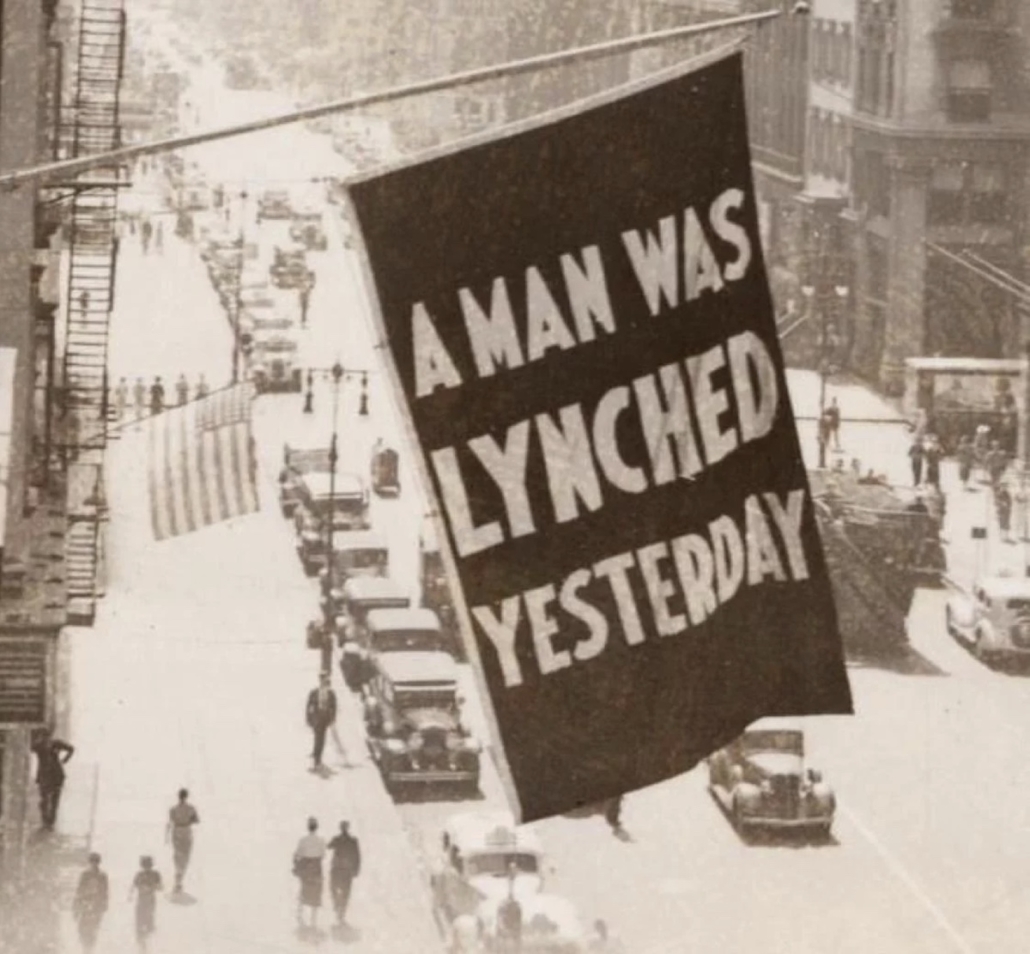

NAACP banners were displayed in many northern cities in the 1920s to draw attention to the horrible reality of social lynchings in the south.

The 1896 Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Fergusen establishing the “separate but equal” doctrine legalized institutional segregation and gave legal cover to all forms of racism and segregation, both de jure and de facto.

A 1904 Journal and Courier headline read “Race Riot in Little Falls.” It seems likely that there was a small colony of Blacks living somewhere “below the aqueduct.” This encampment was routed by some number of white Little Falls residents, possibly fearful about competition for factory jobs. Was this attack the work of a racist minority of white Little Falls residents, or did it reflect a pervasive community sentiment? One can only speculate.

In 1909, the NAACP was formed as an interracial organization to promote justice and equality for Black Americans and to combat racism and segregation. W.E.B. DuBois and other prominent NAACP leaders were responding to surging anti-Black violence throughout the country.

The 1915 silent film BIRTH OF A NATION, portraying blacks as illiterate and the KKK as a heroic force, strongly influenced American society and led to the rebirth of the Klan.

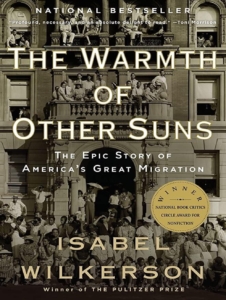

Isabel Wilkerson’s seminal book THE WARMTH OF OTHER SUNS chronicles the 1915-70 northward migration of thousands of southern Blacks to escape poverty, discrimination, and violence. Most Blacks migrated to larger northern cities, but the Little Falls Black community had also expanded in the late-19th Century from such migration. The merging of longtime Black Little Falls residents and southern Blacks moving northward was not always smooth. Internal struggle for control of the AME Zion Church between the longer established Black community and newer arrivals from the south was evidence of these cultural differences.

Isabel Wilkerson’s seminal book THE WARMTH OF OTHER SUNS chronicles the 1915-70 northward migration of thousands of southern Blacks to escape poverty, discrimination, and violence. Most Blacks migrated to larger northern cities, but the Little Falls Black community had also expanded in the late-19th Century from such migration. The merging of longtime Black Little Falls residents and southern Blacks moving northward was not always smooth. Internal struggle for control of the AME Zion Church between the longer established Black community and newer arrivals from the south was evidence of these cultural differences.

DEMISE OF THE BLACK COMMUNITY IN LITTLE FALLS

Throughout much of American history, the Black man “lived the last hired, first fired” ghetto existence of a second-class citizen. Perhaps, it can be assumed that Blacks in turn of the century Little Falls experienced this same form of factory job discrimination given that the population of the Little Falls Black community slowly declined at this time?

The 1925 city census showed only four Black households, a steep drop in only twenty-five years. City burial records for this time period show that there were few Black burials. City records indicate that some Blacks died penniless around this time and were buried in the “colored burial grounds” of Church Street Cemetery without grave markers. City burial records show that a number of those buried in that area were infants and young children.

It seems that a number of Black Little Falls residents left, presumably due to some combination of lack of economic opportunity and racism and segregation. A seemingly unanswerable historical question is: Why did Little Falls’ Black population drop so significantly between 1890 and 1920? Did factory owners refuse to hire Blacks? Did white factory workers refuse to work alongside Blacks?

Further evidence of this decline in Little Falls’ Black population is that in 1924 the AME Zion Church was rejuvenated, but in 1934, the structure was demolished. World War II 1941 draft records show that H.J. Luttrell was the only Little Falls Black man listed by the draft board. No Black Little Falls residents served during either the Korean War or the Vietnam War.

The 1920s rebirth of the KKK resulted in increased racist activity in upstate New York. The Klan was not only racist, but also anti-Catholic and nativist. With increasing immigration to America from southern and eastern European Catholic countries, such as Italy and Poland, Klan activity intensified. Al Smith, both a Democrat and a Catholic, was elected New York State governor in 1918, and then reelected in 1922, 1924, and 1926. Smith was also the Democratic candidate for President in 1928, losing to Republican Herbert Hoover. The Great Depression began soon after Hoover’s inauguration.

During the 1924 gubernatorial campaign and election, KKK cross burnings were a common sight in the Mohawk Valley. KKK posters were put up in Ward Square (Eastern Park) and St. Mary’s Cemetery. KKK meetings and rallies took place in surrounding communities, including Dolgeville and Salisbury. On election night in 1926, cross burnings were seen throughout the Mohawk Valley; perhaps most disturbing was the absence of any community leaders speaking out against this horrible public behavior. The official silence was striking.

1950s AND 1960s CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

The 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas reversed the 1896 Plessy ruling by outlawing segregation in all public places. A stronger civil rights movement emerged soon thereafter. While there was no sizable Black population residing in Little Falls at this time, it is important to understand this most important period of United States history in order to grasp the importance of the 2015 placement of the Church Street Cemetery monument recognizing the African American burial grounds located there.

Black World War II soldiers returning home to southern states after their military service in largely segregated units realized that nothing had changed, racism and segregation still ruled. They had gone to war in Europe and the Pacific to fight for democratic values only to return home and still be treated as second-class citizens.

President Truman used executive orders in 1948 to integrate the federal workplace and the armed forces, setting the stage for the 1950s-60s Civil Rights Movement. The 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas both reversed the 1896 Plessy ruling and gave impetus to early civil rights workers and protestors.

In December 1955, a Black woman named Rosa Parks boarded a public bus in Montgomery, Alabama and refused to “go to the back of the bus” reserved for Black riders. This relatively simple action inspired a revolution by demanding “equal protection of the laws” be made a reality in American life. A year-long bus boycott led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ended with a Supreme Court case declaring segregated public facilities unconstitutional.

Acts of civil disobedience against unjust segregation laws spread across the south. The church-based Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) all emerged as forces for social justice. Televised images of non-violent protestors being beaten by white mobs while law enforcement officials looked on were broadcast into the homes of tens of thousands of Americans. Television accomplished much of what newspaper articles and still photographs could not.

Deeply segregated southern cities like Selma and Birmingham, Alabama, and Meridian, Mississippi became the targets of the twin strategies of creative tension and civil disobedience. Protestors used this form of non-violent protest in the most segregated southern cities knowing full well that violence, beatings, and jailings would follow.

Civil rights protestors went to such cities in large numbers at great personal peril. This one-sided violence was captured by television cameras and broadcasted into American homes during evening news broadcasts. These televised images helped sway public opinion in favor of non-violent civil protestors while also prodding elected officials to enact legislation protecting the rights of Black Americans.

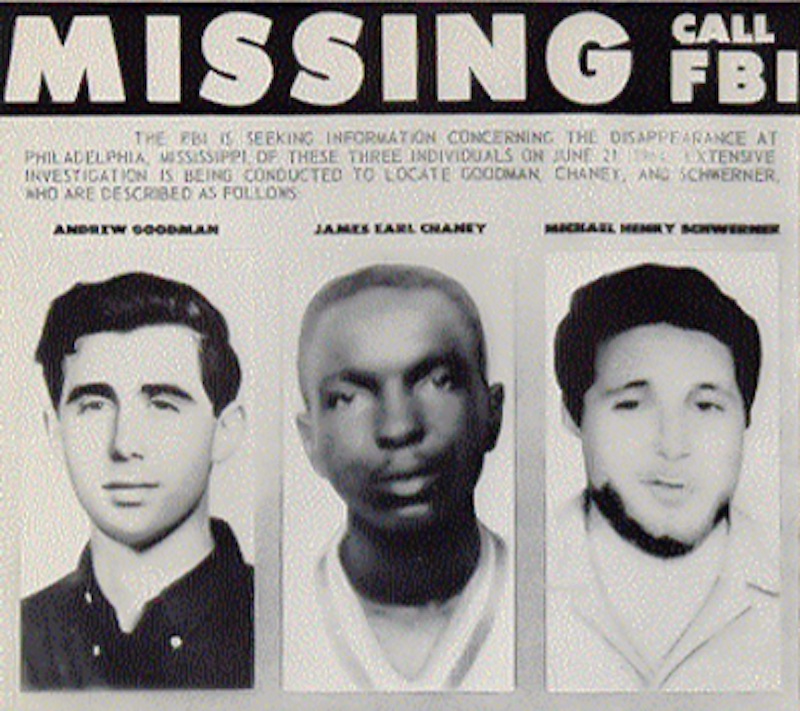

Such was the case in June 1965 when two New York City college students, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, travelled to Meridian, Mississippi to work registering Blacks to vote. In Meridian, they worked with local activist James Chaney to help register Black voters. Driven by compassion and conviction, these three individuals were brutally beaten and killed by local Klansmen.

Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney and Michael Henry Schwerner were murdered in Mississippi while working to register Black voters.

Goodman’s family spent their summers in the Adirondacks near Bog River Falls which flows into Tupper Lake. Litchfield Mt., outside Tupper Lake, was renamed Goodman Mt. in honor of this courageous, selfless young man and his sacrifice to advance racial equality.

The Civil Rights Movement accomplished much during the Kennedy and Johnson presidencies. The 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawed segregation in public facilities and the 1965 Voting Rights Act outlawed various practices aimed at keeping Blacks from voting. The 1964 24th Amendment outlawed poll taxes.

Freedom Riders were civil rights advocates who rode interstate buses into southern states in the early-1960s challenging the non-enforcement of Supreme Court decisions calling for the integration of all public facilities, including public transportation. Freedom Riders used non-violent civil disobedience against Jim Crow segregation laws. On multiple occasions, they were met by KKK mob violence, badly beaten, and often jailed for these actions for having challenged the status quo by riding public buses in mixed race fashion.

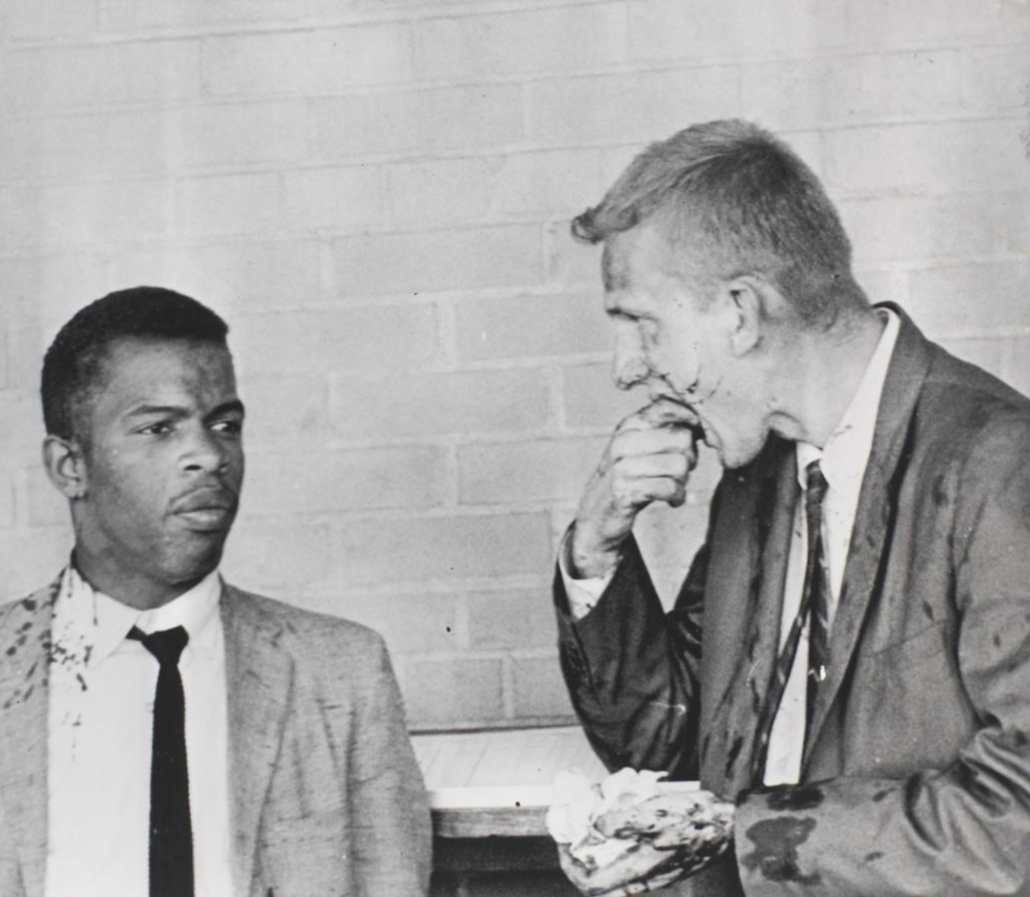

John Lewis (future Senator John Lewis, Democrat, Georgia) and Andrew Zwerg (removing broken teeth) after being beaten along with other Freedom Riders in 1961 in Montgomery, Alabama.

Locally, Bob “Chunky” Champion was a very creative and artistic African American member of the Little Falls High School class of 1950. Champion both created the high school flag and designed the artwork for several yearbooks while in high school.

AUGUST 16, 2015 MONUMENT DEDICATION CEREMONY

Former Little Falls city historian Edwin Vogt undertook a mission in 2013 to acquire and put in place a monument recognizing what had been formerly known as the “Colored Burial Ground” in Church Street Cemetery. Vogt reached out to the Little Falls Historical Society for assistance with this quest. In turn, members of the Historical Society reached out to local funeral director Harry Enea for assistance with the monument project.

African American Burial ground in Church St. Cemetery. Despite the few gravestones, at least 77 individuals are interred in this section.

The combined generosity of Enea Family Funeral Home, Burdick Enea Memorials, and the Historical Society made the acquisition and installation of the monument possible. The dedication ceremony was an important event in Little Falls history.

The ceremony included a religious invocation by Father Thomas Vail (since deceased) and addresses by Reverend Robert Williams of Utica’s Hope Chapel of AME Zion Church, then Historical Society president Louis Baum, and Vogt’s daughter Patty Sklarz. Then Little Falls Mayor Robert Peters next accepted the new monument on behalf of the City. The playing of TAPS by Dr. Oscar Stivala closed the ceremony. Thus ended a remarkable event. The placement of this monument represents an attempt to make up for a past community injustice.

The monument’s inscription reads: “In memory of those early African Americans who were discriminated against in both life and death. Denied equality, few gravestones exist in this section referred to as ‘Colored Burial Ground.’ It is for us, the living, to rectify this wrong by granting this tribute of remembrance and respect.”

African American Burial Ground monument dedicated in 2015 ceremony in Church St. Cemetery.

2015 – PRESENT

Race relations in America continue to pose consequential societal challenges. Published in 2019, the New York Times magazine 1619 PROJECT sought to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of our political narrative, a sort of national reckoning around race. This perspective on early American history has resulted in a conservative backlash across the country.

Whatever historical perspective and interpretation that one employs regarding America’s troubled racial history, the issues of race relations and equal opportunity for all Americans continues to create political and social divisions.

The creation of the national Juneteenth national holiday recognizing the official 1865 ending of slavery in the entire nation was officially created by President Biden in 2021 through an executive action. Juneteenth joins Martin Luther King Jr. Day as two federal holidays recognizing Black struggles throughout American history.

The national 2020 census revealed that Little Falls has less than 1% of its population self-identified as Black or African American / non-Hispanic.

INDIVIDUAL AFRICAN AMERICANS BURIED IN CHURCH STREET CEMETERY

MRS. DEAN MILLER – There is little that we do know about the life of Dean Miller and much that we do not know. At the home of George Herkimer, formerly owned by his brother General Nicholas Herkimer, a birth record was found “Born to my wench on this 18th day of April 1802, a female named Dean.” Unfortunately, the mother’s name was not recorded – it is thought to be Jackson. The birth was recorded by Alida Herkimer, George’s wife. Dean remained at the Herkimer farm until her marriage to Abram Miller.

Dean had one child who died when about a year old, after which she and her husband moved to Little Falls. Her husband passed away in 1848. Dean then became employed for a long time by the well-to-do Sanders Lansing family on Church Street. She was described as a devoted Christian who commanded the respect and admiration of all who knew her; she was a familiar figure upon the streets of Little Falls. After the death of her employer, she was given the use of a cottage on the grounds for the remainder of her life.

Dean passed away on October 18, 1876, at age 75, and was buried next to her husband in the “Colored Burial Ground” at the northern section of Church Street Cemetery. She was held in such esteem by the Herkimer family that three descendants, Mesdames Johnson, Gilbert, and Greene, installed a beautiful monument at her gravesite.

THOMAS WILSON – The February 9, 1865 edition of the Little Falls Journal reported the death of Thomas Wilson, “A few days since ‘Uncle Tommy Wilson,’ a “colored” resident of this village and one of its early settlers died suddenly while sitting in Smith’s Saloon.” It went on to say, “He had reached the ripe age of 96 years and was universally known and respected by our citizens as an industrious and honest man.” Other information indicated that he worked as a laborer and had died of heart disease.

REBECCA BATTISON was born in 1774 in Virginia, the daughter of slaves. Little is known about her early days. She came to Little Falls with her granddaughter Sarah who was married to George Dygert. Mr. Dygert is buried in the “Colored Burial Grounds” at Church Street Cemetery. Rebecca worked most of her life as a “white washer” or laundress. The 1865 census listed her as “head-of-household” and a property owner. The 1885 census stated that she was 111 years old and blind and crippled. An article in the Little Falls Journal & Courier on May 9, 1883, indicated “If she lives to next Thursday, Rebecca Battison will see her 114th birthday which will be celebrated at an event at the Cronkhite Opera House.” Legend has it that she heard friends talking about being at President George Washington’s inauguration in New York City in 1789, as well as other important events in the early history of the nation. She would have been around twenty years old at the time. Because of their elderly age and status within the African American community, Rebecca, along with Mrs. Dean Miller and Cecilia Johnson, were held in high esteem throughout the village.

CECILIA JOHNSON was born in Saratoga Springs in 1809. In 1850, Cecelia and her husband Thomas lived in the household of George Entley, an African American barber. In 1851, they all moved to Little Falls where Entley opened a barber shop. By 1854, Entley was qualified to vote since he had three years residence in the village and had real estate valued at over $1,000. However, he died before he could exercise his right to vote, and Cecilia Johnson was named executrix of his estate. Thomas then reopened the former Entley barber shop in July 1855 (most of the barbers were African American, one of the few trades available to Blacks) and Cecilia opened their large house to family and friends. It was not uncommon for multiple families to live under the same roof. The 1855 census showed Cecilia as head-of-household. Living at the house were her husband, mother, daughter, son-in-law, five grandchildren, and two nephews. Over the next 30 years, countless relatives, friends, and tenants lived there. In addition to running the household, Cecilia worked as a white washer or laundress well into her seventies.

ENOCH AND CORNELIA MOORE – In 1851, Enoch Moore was persuaded to move from Troy to Little Falls with his family by the Black community leader Reverend Jermain Wesley Loguen to help establish a Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church in the village. Little Falls was an important location because it was half-way between Syracuse and Albany with the Erie Canal and railroad nearby. In addition to furthering his work at the Zion Church, Enoch, known as “the Colonel,” was an outspoken advocate for full constitutional rights for Black people. Despite his and other residents’ efforts, Black suffrage was voted down regularly by large margins of Little Falls voters between 1846 and 1869. During this time, he attended Black conventions across New York State agitating for suffrage. The 15th Amendment legislated Black suffrage in 1870. During the Civil War, Enoch actively recruited forty-five men for service in the 54th Massachusetts “Colored” regiment. When he died in August 1882, Enoch was the voice of the Black community and his philanthropy and tireless work on behalf of his people and church were universally acclaimed. His funeral services were held in St. Paul’s Universalist Church.

Cornelia Moore was also born in Troy and came to Little Falls with her husband Enoch and their family in 1851. They established residence in a large home on Furnace Street with their three daughters (a fourth was born in Little Falls), the family of Reverend James Bosley, and three boarders. Little Falls had only a small Black population and there was little segregation. Cooking for large numbers soon became a business. Cornelia, assisted by Enoch, became one of the most sought- after caterers in the Mohawk Valley for receptions, parties, galas, weddings, and other events. She was also assisted by her daughter Ida who was also considered an excellent caterer. Cornelia continued the business after Enoch’s death and held the esteem, honor, and respect of the entire community. When she passed away in January of 1913 at age 80, her obituary contained her photograph, something usually reserved only for elite whites. Initially, she was buried in Church Street Cemetery, but her remains were later moved to Fairview Cemetery.

CHARLES PETERSON was a barber in Little Falls who married Ida Moore, the daughter of Enoch and Cornelia Moore. Originally a Utica native, Charles was active in civic affairs and a member of the “colored” Masonic Order in that city before moving to Little Falls. Peterson became famous in the central Mohawk Valley and state-wide for his elegant “Colored” Balls and Cake Walks, drawing Black people from all corners of the state. Balls in Little Falls were held at the Cronkhite Opera House, Skinner Opera House, Grange Hall, and Washington Hall to packed audiences with upper-class whites in attendance as spectators. In addition to these balls, Peterson sponsored summer Black camp meetings at local picnic venues. He lined up vendors (mostly white businesses), brought in preachers from near and far, and special entertainment from New York City. Many whites attended these summer events. Charles and Ida’s son Clayton (Clay) Peterson was born in Little Falls in 1881. He attended Church Street Grammar School, and he excelled in football, baseball, and track and played the drums in the school band. Clay did not finish school, and as a young man worked as a gardener and coachman for a local family on Ann Street. He then worked for most of his career as a pressman at the Journal & Courier Co. Clay never married and lived for several years with his Aunt Belle Moore on Furnace Street. After his aunt’s death, he lived at the YMCA. Clay died in 1971 at age 90. With his passing, the last connection to the old Black community in Little Falls was gone. An important era in Little Falls history, a period of over 150 years, had come to an end.

CONCLUSION

Researching and writing this article has been a most rewarding experience for the various Historical Society members who contributed to this effort. While the primary purpose of this undertaking was to chronicle Black Little Falls history, it was impossible to write this story without intertwining local people and events with broader state and national history.

Special thanks are extended to Richard Buckley for giving permission to use his great Little Falls history book entitled UNIQUE PLACE, DIVERSE PEOPLE as a quality resource for this article.

This article is the byproduct of a collaboration between various researchers, writers, and editors, all members of the Little Falls Historical Society.

WRITERS

- Jeffrey Gressler

- David Krutz

- Louis Baum

RESEARCHERS AND EDITORS

- Anita Dulak

- John Frazier

- Pat Frezza-Gressler

- Gail Potter

- Ginny Rogers

- Michael Smith

- Missy Smith

- Pat Stock

- Maryanne Terzi