He Still Sustains: Pitt the Painter’s Studio Loft by Laura Laubenthal

From 2011 to 2013, I wrote my master’s degree thesis for the Cooperstown Graduate Program about “Pitt the Painter” and his role in showcasing the identity of Little Falls by means of his artwork. The project was largely based on oral histories told by those in town who remembered him since his death on September 4, 2007. While I spoke with several people, there were so many more I did not reach, as Pitt’s sphere of influence seemed immeasurable. The project went on, and it was apparent that these stories meshed together as modern-day folklore about talent, humor, addiction, and belonging.

When I wrote the thesis, I was only able to see the exterior of Pitt’s studio loft at 56 West Mill Street. The building originally housed Andrew Little & Sons Lumber Company and was later occupied by Little Falls Construction downstairs while Pitt lived and worked above. By the time I reached the scene four years after Pitt’s death, however, 56 West Mill Street sat locked and vacant, with remnants of Pitt’s work still painted on the panes of window glass which had not yet broken from vandalism and neglect.

Photographs remaining in Pitt’s old studio loft at 56 West Mill Street, now in the possession of Mike George, Ironrock Brewing Co.

Years later, 2020 proved to be a time of growth amidst hardship. Mike George, of the George Lumber family, purchased 56 West Mill Street in 2018 and opened Ironrock Brewing Company during the pandemic. The brewery has had great success in spite of mandated state shutdowns and social distancing measures. As I became acquainted with Mike, I mentioned that I wrote the thesis about Pitt. Mike revealed that Pitt’s loft was far from empty when he purchased the building and he allowed me to go upstairs once in November 2020 and again in April 2021. The loft was largely untouched in November and the walls were scrawled with Pitt’s sketches of Jack Nicholson, prices and addresses for various commissioned signs, and Latin epitaphs. The room was littered with a massive project table, a few brushes, and several papers. By April, Mike had undertaken significant repairs to the walls and ceiling, as the room was plagued with water damage and surrounding beams were licked by flames from a fire many years before. Still, the paint-spattered wood floor remained, as well as Pitt’s easel and almost two hundred Kodak photographs depicting artwork and people in social settings; many presumably taken by Pitt himself from the 1970s to the early 2000s. These surviving objects allow Pitt to tell his own story.

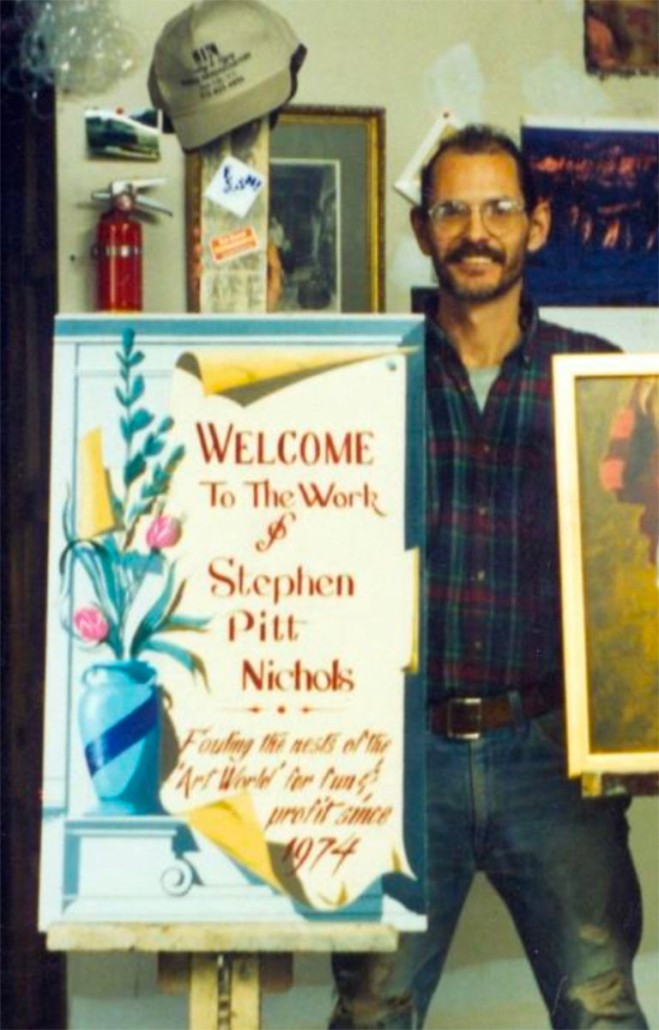

“Welcome to the Work of Stephen Pitt Nichols: Fouling the nests of the ‘Art World’ for fun & profit since 1974.” Photograph from the collection of Stephen Pitt Nichols, now in the possession of Mike George, Ironrock Brewing Co.

Stephen Pitt Nichols was born on January 21, 1951 in New Haven, Connecticut to John “Jack” Roy and Opal Holland Nichols. Little is known about his early life in Connecticut, other than the fact that he had two younger twin brothers, one of whom became a painter by trade. At the end of his teenage years, Pitt attended the School of Music at Little Creek in Norfolk, Virginia for flute. He then served in the U.S. Army from 1969-71. His position in the army band allowed him to avoid entering conflict in Vietnam. It is also likely that Pitt attended the Paier Art College in Hamden, Connecticut sometime in the early 1970s for formal art training, but no records from the school survive to prove he attended; perhaps because Paier had not become a four-year degree-granting institution until 1982. A photograph found in the loft, however, suggests that Pitt began creating art as his livelihood in 1974.

By the late 1970s, Pitt ended up in Schenectady, New York as a landscaper at Union College. He was an avid baseball fan and enjoyed watching the Union College baseball team. On one momentous occasion in the early 1980s, Pitt followed some of his friends on the Union College team to watch the Little Falls Mets play a home game. After the game ended, Pitt remained in Little Falls. He quickly enmeshed himself in local society by frequenting public spots and engaging in conversation with notable townspeople. He found all facets of society equally interesting, and enjoyed talking about politics, literature, and current events. Once his talents as an artist came to light, people began calling him “Pitt the Painter.”

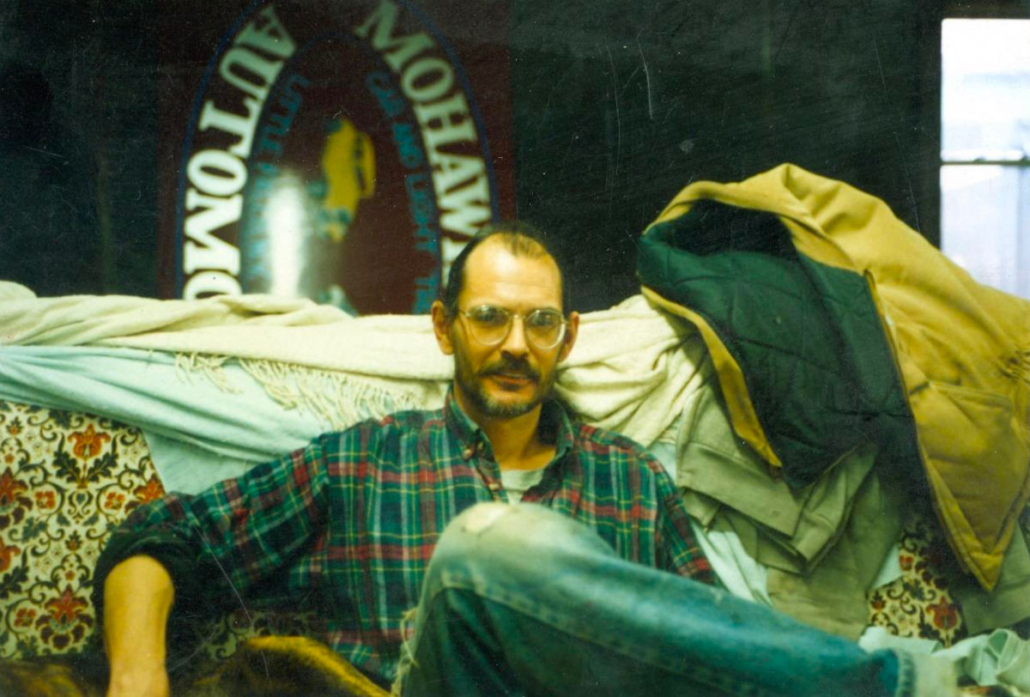

In the early 1990s, Pitt took up residence in the loft at 56 West Mill Street, bartering window decals, business signs, and odd jobs for his tenancy. A photograph dating roughly to that time provides a glimpse of Pitt’s studio setup. It was cluttered, yet logical; and active, with projects at various stages of completion and several yellow cans of “1 Shot” brand paint at the ready. One can almost envision the cans and brushes rattling on the table as Pitt paced across the floor, dragging and sawing plywood sheets, or playing his flute erratically, much to the dismay of the business operations of Little Falls Construction below. Pitt developed a large local clientele while living at the loft. As a result, people from all walks of life poured into the Little Falls Construction office to visit Pitt upstairs. Customers, though always satisfied with the quality of Pitt’s work, were rarely pleased with the length of time he took to produce it. They often inquired about the status of their orders. Pitt was a perfectionist, and, consequently, he never felt his paintings were finished. His alcoholism sometimes slowed the output of his work. During his benders, customers pounded on the door to demand their commissions. Pitt sobered up long enough to paint what he promised.

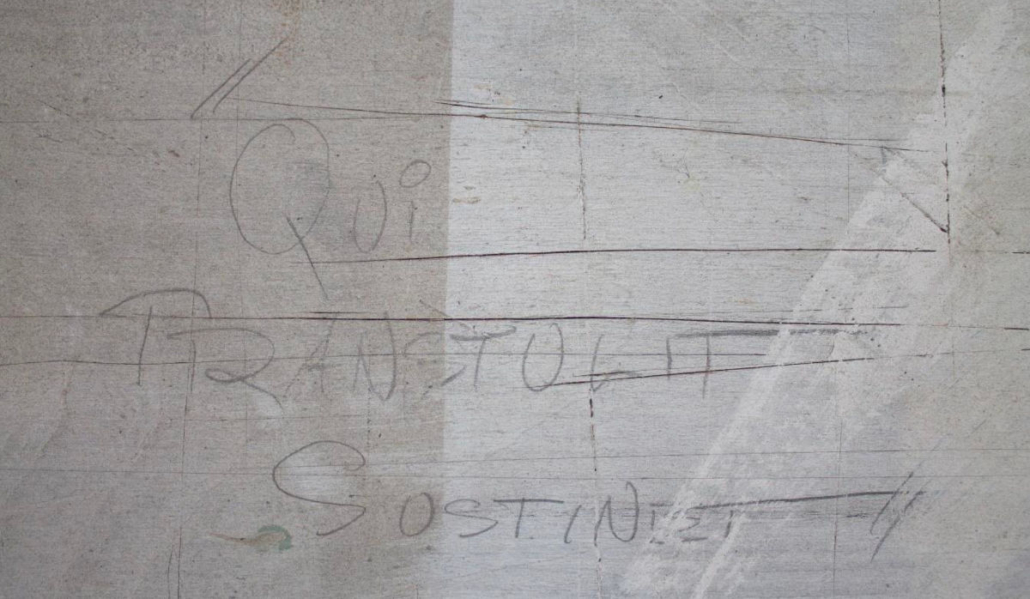

In 2021, the loft is nearly empty, but familiar light spills in through the windows. Pitt’s easel stands like a beacon, scarred with outlines of paint from numerous past projects. Upon closer inspection, one can see that Pitt wrote in Latin on the front of the easel, just next to where a work of art would sit: “Qui Transtulit Sustinet,” or “He Who Transplanted Still Sustains.” This phrase happens to be the official colonial motto of Connecticut, Pitt’s home state. It suggests that he kept a connection to his roots, but also speaks volumes for his transient habits. The phrase implies that a person will survive regardless of his or her location. Perhaps, any place can become home with some effort. Whether by means of intelligent conversation, antics, or his artistic output, Pitt sustained himself in Little Falls. Additionally, the surviving Kodak photos prove that he made an artistic impact on a much larger geographic radius including Schenectady, Mohawk, St. Johnsville, Otter Lake, and other locales.

“Qui Transtulit Sustinet,” Connecticut state motto once written by Pitt on his easel, seen in April 2021.

Some of Pitt’s early work referenced his roots. Found among the photos is a 1981 sketch depicting an unknown female relative entitled “First Cake.” The sketch was based on a black and white family photograph from the 1930s-40s. The same year, Pitt completed a more complex finished pencil drawing of the subject. The drawing now belongs to Jim Drebitko, a friend whom Pitt met while living in Schenectady. Today, one can only conjecture why the topic of a woman’s first successful bake was so important to Pitt.

The print which currently rests on Pitt’s easel, previously strewn amongst other papers in the loft, is particularly poignant. It proves that Pitt was a published artist: a revelation I had not known when I wrote my thesis ten years ago. Entitled “Things from the Kitchen,” the work was originally painted by Pitt in 1979. While the location of the kitchen depicted in the artwork is unknown, the specific rust spots on the enameled utensils and the dents and dings in the bead board wall paneling suggest it was a real setting, and one that Pitt knew well. He self-published the artwork as a print in 1980 while living in Schenectady. Pitt dabbled in self-publishing as a means to boost his income, but the benign artwork themes he chose to reproduce were not the best choices to appeal to wide audiences. Had he chosen more of his photorealistic landscapes depicting relatable sites in Schenectady or Little Falls, his prints might have sold more successfully. One can deduce that these early setbacks might have encouraged Pitt to give his work a more overtly regional, rather than personal, focus later on. Pitt’s own copy of “Things from the Kitchen” became scrap paper, as evidenced by its rolled condition and a line drawing of a nude on the back side.

Regardless, Pitt still found subtle ways to inject himself into pieces that were more marketable. For instance, no two versions of his iconic “Erie Canal, Little Falls” scene are the same. The ever- changing proximity of the whiskey jug to the man on the packet boat symbolized Pitt’s stage of sobriety at the time he painted each scene. The closer the jug, the greater Pitt’s struggle was. Furthermore, Pitt’s constant renderings of the actor Jack Nicholson likely appealed to fans of the movie star and people bought the artwork because it was a quirky topic. In actuality, Pitt had a wordplay connection to the actor’s name, in that he himself was Jack Nichols’ son.

Regardless, Pitt still found subtle ways to inject himself into pieces that were more marketable. For instance, no two versions of his iconic “Erie Canal, Little Falls” scene are the same. The ever- changing proximity of the whiskey jug to the man on the packet boat symbolized Pitt’s stage of sobriety at the time he painted each scene. The closer the jug, the greater Pitt’s struggle was. Furthermore, Pitt’s constant renderings of the actor Jack Nicholson likely appealed to fans of the movie star and people bought the artwork because it was a quirky topic. In actuality, Pitt had a wordplay connection to the actor’s name, in that he himself was Jack Nichols’ son.

Pitt’s Erie Canal scene and lettering on a Little Falls ambulance, early 1990s. (Note the whiskey jug immediately to the left of the boatman). Photograph from the collection of Stephen Pitt Nichols, now in the possession of Mike George, Ironrock Brewing Co.

Mike George was kind enough to allow me to scan all two hundred of Pitt’s photographs from the loft at 56 West Mill Street. In the future, I plan to assemble a self-guided tour featuring the historic images of Pitt’s artwork in comparison to the same vantage points today. Although it has been fourteen years since his death, Pitt’s legacy is still present in Little Falls. He left us with daily physical reminders in the form of his artwork and personal belongings. While some of Pitt’s signs have succumbed to theelements over time, the impressions he left upon many townspeople have not yet faded. He who transplanted still sustains.

Photograph from the collection of Stephen Pitt Nichols, now in the possession of Mike George, Ironrock Brewing Co.

Laura Laubenthal is a member of the Little Falls Historical Society. She received her Master’s degree in Museum Studies from the Cooperstown Graduate Program / SUNY Oneonta. The Historical Society has collaborated with Cooperstown Graduate Program students on projects in recent years.